Stepping in as H.R.'s replacement in the Bad Brains was never going to be an easy task, but for a 20-year-old singer named Israel Joseph I, the challenge felt like an opportunity he couldn't let slip by. It was the early '90s and the Brains and their iconic frontman had parted ways, which was a huge disappointment since the band's previous album—1989's Quickness—had been celebrated as a gem of the era.

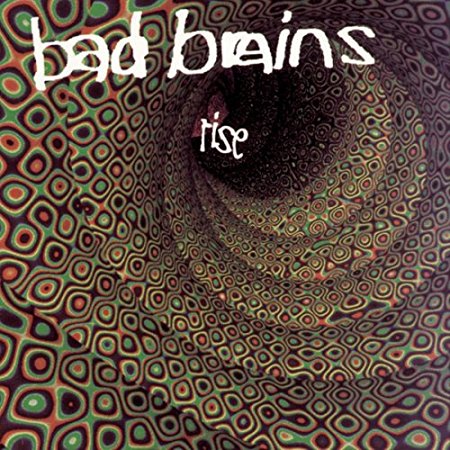

When it was announced that an unknown musician was going to be the group's new singer, skepticism was high within the Brains' fanbase. It didn't help matters that the influential punk outfit had also revealed that they had signed with the suits at Epic Records for their next studio effort. But instead of letting the noise hamper his outlook, a young Israel channeled his energy into co-writing most of the material that would end up comprising Rise, the Brains' fifth studio album, and his debut with the band.

Israel only lasted one album with the Brains, but his musical journey didn't end there. In this new interview, I speak with the musician about his time in the influential group, the circumstances that led to his decision to leave, and his life since that period. It was the first time I had ever chatted with Israel, and I found him to not only be an extremely open person, but also a positive one who is at peace with his past.

As much as I pride myself on my music trivia knowledge, I have to admit that I don't know much about you. I guess the best way to start this is to get some background on your childhood.

I was born in the little Caribbean island of Trinidad. I was raised there in a kind of upper middle class kind of family. My mother worked for the American embassy and I grew up with my family having parties at our house every weekend. We listened to calypso and reggae, and all kinds of American music from rock to soul. My father was a huge fan of music and worked on the oil fields. He used to play records every weekend. It was the '70s and everyone was having a great time. I was always into music and I remember standing in front of my dad's speakers and staring at the way the bass shook them. So, yeah, I was always drawn to music and the effect it had on people.

How old were you when your family left Trinidad?

We moved to New York when I was about 8, and things fell apart for us in a few years. We ended up in abject poverty in a bad part of New York you probably don't know of.

I'm from Queens, so you might be surprised.

It was a place called New Cassel on Long Island, right next to another town called Westbury, it's actually not that far from Queens.

New Cassel? Whoa! I remember going there with some friends who were from out on the Island back in the early '90s. That was one of those neighborhoods where you could score drugs easily. I've always said that if there's a ton of bodegas within a few miles of each other, I don't care how suburban the place is, it's still the hood.

[Laughs] okay, so you know what's up! Yeah, even though it was Long Island, it was still "protect ya neck" out there. Anyway, that's where I grew up and I remember turning to rap music right away. By 1983, I was rapping in school and I had a natural knack for it. I was into it all: rapping, breaking, anything hip-hop. I didn't know anything about hardcore punk at that point.

SEE ALSO: 2016 interview with Don Fury (Producer: Judge, Quicksand, Gorilla Biscuits, Underdog, Inside Out).

How did hardcore and punk music enter your life?

Well, I failed 8th grade, because I was having some family troubles at home, and I was bored as well. After that happened, my family sent me away to Toronto, Canada to live with my brother for the summer. It's there where I first met people who looked like and listened to punk. I got really into the music and when I came back home to Long Island, I was a different person. My friends were like, "What happened to you up there?!" I mean, I still listened to hip-hop and I'm still rhyming, but I'm also into this other music. Anyway, that started a rift with some of my friends.

Yeah, that sounds familiar.

Yes, so that's when I started going into Manhattan with my friend Eric Ajero. He was my best homie, a Filipino dude who knew everything about punk rock! He used toothpaste to stiffen his foot-tall liberty spikes. We were in the hood, but he didn't care. I gravitated toward him. Anyway, one day we're in his house, smoking some weed, and he goes to me, "Oh, you're growing your dreads out? You trying to be a rasta now?" He was just joking around, you know, friends messing with each other. But then he says, "You're not a real rasta because you don't know the Bad Brains." I'm like, "The Bad who?" You know what I mean?

So you weren't even familiar with the Bad Brains at that point. What year was this?

This was in 1987, I was 16. Yeah, I was heavily into music, and heard so much stuff, but I had never come across the Bad Brains by then. So he goes into his record collection and takes out I Against I and lends it to me. Carlos, I remember going home and playing that record and thinking it was really, really great. A couple of weeks later he played me the ROIR cassette and that changed everything.

Is that the time period when you began performing on the live circuit?

Yeah, I was playing in bands, doing hip-hop, working in studios. I didn't do live stuff with the hip-hop, but the reggae band I had with some friends from school played live a lot. We had a song called "Tightrope," and it was dope. Man, we had it going on!

What was the reggae band called?

[Thinks for a few seconds] I can't remember the name of the band right now! I had a concussion and it messes with my memory. But I also played in a metal band called Common Thread. Yeah, I was doing everything back them [laughs].

SEE ALSO: 5 Underrated Funk Metal Bands

What did your mom think of your involvement with music at that point?

I grew up in a strict family but once we came to New York, it was like bam! So, she was dealing with that fact that she wanted me to still be like we were back in Trinidad yet having to get accustomed to the way of life in New York. Me and my brothers were changing because of it, but even more in my case. From a young age, the only way I felt I could really see my way out of the hood was to be an artist. I didn't have skills playing ball. I didn't think I was going to be able to excel at school enough to get through college. I knew I had the ability, but I couldn't focus. I had OCD from an early age, but they didn't diagnose that kind of stuff back then. My mom acknowledged that I was different, but being into punk and all that wasn't the way she wanted me to be.

As a parent, I know how your mom must have felt on some level, but it sounds like music saved you. When did reggae become important in your life?

That summer, my friend Chauncey came home from college with a copy of [Bob Marley's] Natty Dread and that was a huge turning point for me. Before then, I had never known of people from the Carribean getting respect. It was always like, "You come from Trinidad? Did you live in a hut?" But listening to Bob Marley, he had a dominant spirit to everything he did. I was attracted to it, spiritually. My grandmother schooled me hard on the scriptures when I was very young, so I understood what Bob was writing about. By the end of that summer, I was a rastaman vibration. I gave up meat, and I was the biggest meat eater in the house back then! Yeah, everything changed after Bob.

Did your music begin to reflect that change?

Yes, I got a band going called Uprizin and that's kind of how I got connected to the Bad Brains later, because I met a girl at one of our shows named Latasha Diggs. She's the person who eventually told me about the Bad Brains' vocalist auditions. But, yeah, that reggae band did really well and we played to big crowds. I also became more of a confident performer. I understood things on a different level. Actually, both I and the Brains were changed by the music of Bob Marley. We had many conversations about it when I was in the band.

Alright, let's get into the Bad Brains chapter of your life. How did you come to join the band in the first place?

Like I mentioned, my friend Latasha had auditioned for them, but I never did. Before I even joined, I had gotten to be friends with [Bad Brains vocalist] H.R. after going to see him play some solo shows. But that had nothing to do with it. In 1991, Latasha had heard through the grapevine that the Bad Brains were going to be holding vocalist auditions at [famed NYC music venue] S.O.B.'s. So she goes down there to try out and then tells me about it after the fact. She wasn't sure if she got it or not, but she was happy that she got to meet [Bad Brains bassist] Darryl Jenifer. She goes on to tell me that she told Darryl that she knew someone who would be great for their band and gave him my phone number. I couldn't believe it!

She's like, "Yeah, when we drive around you sing along to the Bad Brains and sound just like H.R.!" She thought that if they heard me sing, they would get it. Latasha was the one who really did it for me. She believed that I could do it.

But I'm sure you never thought Darryl would actually call you. I mean, who would?

Yeah, about a month passed by and I forgot about the whole thing. I'm a stoner, so I probably forgot about it about a week later [laughs]. But one day I'm sitting in my mother's house and she answers the phone and then passes it to me. I hear this deep-ass voice on the other end who says, "Hello, is Israel there? It's Darryl Jenifer from the Bad Brains." Straight-up, Carlos, just like that. I thought it was someone playing a joke on me, but then it all came back to me: "Latasha gave you my number!" We started having a conversation about life, music, the Bad Brains, everything.

So he invited you to try out for the Bad Brains during that first call?

Darryl told me that they were living up in Woodstock, which blew my mind since I figured they all lived somewhere in the Lower East Side or something [laughs]. He invited me up to hang with them the following week. So, I took a bus to Kingston, NY and met them for the first time, which was a trip. Man, it felt like I was hanging in the middle of an album cover all that night [laughs]. We had such a great time. We got along immediately. Nothing about the hang felt contrived.

When did you get to actually jam with them for the first time?

Well, we got up early the next morning and went over to their rehearsal spot which was a big old barn. It was really cool, with a stage and everything. Once they warmed up, they asked me, "What song do you know?" I told them that I knew every one of them. They then said, "Come on, man, for real." So I told them again, "Everything." The next thing they said was, "Okay, let's do 'Reignition.'" I started singing it and we sounded great together.

Then they started playing "Soul Craft," and I started doing the [imitates the vocal scat intro from the song] and Darryl stops me, "Hey, wait a minute, that's my part!" Anyway, we started the song again and in the middle of it, they stop playing. I thought I was doing good and I was nervous that I had maybe messed up, but that's why they stopped, because it was sounding really good [laughs].

Wow, so they probably were surprised how solid it was already sounding.

Darryl says, "Yo, Doc! He sounds just like H.R. When I'm closing my eyes, it sounds just like him singing." I told them that, yeah, I could imitate him 'cause he's got such a fun voice to sing along to. It's like a playground for kids, I could climb all over his voice. It's vocal gymnastics. Then they asked me if I wrote music, and once I told them that, they basically gave me the job right then. We spent the entire day jamming and within a few weeks after that, we started playing shows.

How did the writing process work itself out?

There came a day when Darryl says to me at practice, "Israel, call out a note." I yell out, "B-flat!" Then he plays this loud chord and tells me, "We're about to write a song." That was the beginning of what ended up becoming the song "Rise." We started with that song and ended up having three others: "Strength in Numbers," "Miss Freedom," and "Free."

So things were flowing nicely.

Yes, after we had those songs done, we decided to make a demo. Once that demo got out there, everything broke loose. People started calling us right after that. The music industry came calling, but at times we weren't sure if they loved the demo, or they just wanted the Brains. It was a crazy time.

How old were you when that was happening?

I was 20 [laughs].

What was the age difference between you and the rest of the band?

It was about 10 years.

Why did you decide to strike a deal with Epic Records?

When we were talking about the record deal thing, we decided that the best thing for the band, and the best way to spread the rastafari message, was to be on a big record label. I was the one really pushing for that. Being young, I had this new vision like, "Man, small labels are great, but you've been doing that for years. We gotta do something big now and blow it up!"

After you signed with Epic Records, you entered the studio with producer Beau Hill. I remember thinking that it was an odd choice to go with him since he was mostly known for working with melodic hard rock acts like Ratt and Winger. The union ended up working, but it seemed like a crazy collaboration on paper.

Well, we had these big label-type of producers looking for us since we had signed with Epic. We could have gone with Ron Saint Germain because he did the previous album, but I was feeling we needed a different sound, and Doc felt the same way. Darryl was actually the one who brought up Beau Hill. I had never heard of him, but I had heard a lot of his stuff, I just wasn't aware that he had done those records. But once I started really listening to some of his productions, I was blown away by his work. He got a really cutting guitar sound on his records. I started thinking that bringing his style to the Brains could be amazing. It could also be a disaster, but if it worked, wow. So we agreed with giving him a chance, but I definitely pushed for him the hardest.

SEE ALSO: 10 Cover Songs That Surpass Their Originals

It sounds like even though you were the new guy, they really put trust in you from the start.

You know, Carlos, they were letting me make a lot of decisions, and I don't know why. For example, I chose the album cover, you know, the swirl tunnel. But they were really supportive of my ideas, yeah.

How did Mackie Jayson end up playing drums on the album?

Mackie came in because Earl was having trouble traveling at that point. By the time Earl started getting there, Mackie had already written all these drum parts, so it became his thing. But we did play extensively with Earl and toured with him. But, yeah, Mackie played on the record. Mackie is a machine. He's unreal. It was a pleasure playing with him.

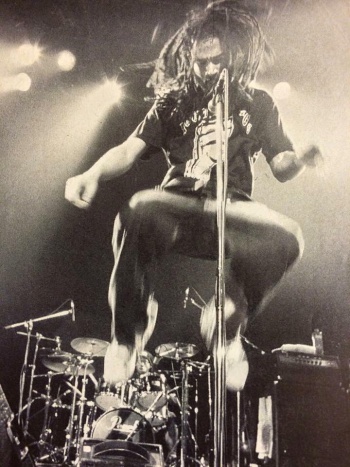

When it came time to track your vocals for Rise, how much pressure were you feeling? I wouldn't blame you for feeling overwhelmed since you were replacing such a massive force in H.R., but when I think about it, maybe your young age at the time might have helped in that regard, giving you a certain amount of cockiness.

I think that definitely helped. What also helped—and I don't mean to sound facetious—is that I felt like I was on a mission. It was almost like I couldn't help but do what I felt was my mission, no matter how people felt about it. I wanted to keep up the positive tradition of the Bad Brains, but at the same time, I had to be me, and if the fans didn't like my voice, that was their choice, and it was okay. But when it comes to the fear, yeah, I think the youth and the punk attitude I had definitely helped me back then.

How long were you guys in the studio making Rise?

We had rehearsed the material so much before we went in to do the album, so it only took us two or three days to make it.

That's nuts!

Yep, even the vocals were done within that time. Beau couldn't believe it. The mix took about two weeks.

The album features a cover of a song called "Hair," which was originally written and recorded by Larry Graham for his band, Graham Central Station, back in 1974. How did that song come on your radar?

We were coming home from rehearsal one day and Darryl played me the original version of that song, and the bass on it was like slap bass heaven. I was like, "What is this?!" Darryl's like, "Come on, it's Larry Graham!" But I had never heard the song before. I was like, "Dude, we need to cover this!" So we ended up working out a rock version of the song and people liked it when we played it live. Either way, that song is a winner, and it was an homage to Larry.

What was your initial impression once you heard the final version of the album?

First I thought that it sounded different from anything the band had done before. That was my first thought. Then I thought that it sounded insane. I turned it up and listened to the sonics Beau captured, you know, the guitars, everything. I was so happy with what Beau captured.

That must have been a rewarding feeling.

Yes, especially since when we wrote the record, Doc and Darryl hadn't been working that much during the previous few years, and there wasn't a lot of money around. We were living close to the earth, if you know what I mean. I listen to that record now and I feel like what I was going through during that time really comes out in the lyrics because we had to rise ourselves. It was all about rising up.

SEE ALSO: When Hardcore Bands Went Hard Rock

How much touring did you do in support of the album?

We were out there close to three years. It was like two months at a time.

How did you handle the road life? Here you were a 20-year-old guy out on the road. Did you live out any of those rock star clichés?

[Laughs] you mean, sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll? Nah, I was with the finest girl at the time, so I wasn't sleeping around on the road. I think I handled everything well, but, yeah, there was a lot of weed. I always made sure we had herb. The shows were insane. We always got the crowd into destroy Babylon mode. You know, having a great time. Some shows were rougher than others, but most of the time we were having so much fun. As a band, we got even closer out on tour.

Why did you end up leaving the Bad Brains?

It was about money. After being with them for about two years, and playing to something like 57,000 people at the Reading Festival, I was wondering why I was only making a little amount of money. I was wondering how other folks are able to have things that I couldn't with what I was making. I wondered if they were getting much more money than I was. That began to be a big question. So, because I couldn't get a straight answer, and it seemed like I was being asked to hire a lawyer, I called up Doc one night and I basically told him I couldn't continue in that manner.

Something else that happened during my time in the band was that I suffered a concussion during one of our shows. It happened a couple of months or so before that call to Doc. What had happened was that I was swimming on top of the crowd and when I tried to get back on stage, someone pushed me too hard and I smashed my dome. I couldn't even see when I first got up. I ended up finishing the show, but I was never well after that. My speech actually got really messed up. So I don't know if that had something to do with my decision to leave the band as well. I didn't even get a proper diagnosis until years later.

Did the band have any new material written before you parted ways?

We actually wrote an entire second album that was never released. There are songs on there that are way crunchy, bro. Like serious stuff, man. There's some bad ass rhythms on there. I had lyrics written and everything.

So you're talking about an album's worth of material that didn't end up on the next album with H.R., God of Love?

Yeah, while I was still in the band, the plan was for us to switch over to [Madonna's] Maverick Records. But what happened was that she didn't want a political album. She wanted more of a love thing, not a rebel album. But I was writing deeper stuff and I didn't feel like censoring myself. That became another conflict I had with the band. I guess the label wanted something more commercial they could sell. I felt like it was a waste, 'cause the material was so strong. It would have been hot. People would have tripped!

SEE ALSO: 2015 interview with Gary Meskil (Crumbsuckers, Pro-Pain).

What are you up to these days? I know you're living out here in Los Angeles.

I have to give thanks to Jah for keeping me alive. I've had some tribulations. I'm a cancer survivor. I had a tumor removed from my upper left shoulder. It was attached to my spine and was very painful for some years. But I'm good now. I've been producing a lot of music on my own since the Bad Brains. I've been doing a lot of solo stuff that I'm trying to do independently due to my past experiences with the music business and not being paid. I ended up in poverty in the late '90s, and not having a good income with the concussion issues was a huge blow. So I moved to Los Angeles and got into construction and had a knack for it. I did well with that and it afforded me the ability to set up a little recording studio. I started understanding how to get a really great sound out of that studio.

You've been releasing all kinds of different music.

Let's see, I put out an album called Rod of Iron, which was a reggae effort where I did everything on it, and I did the same thing for the follow-up. I put out a rap album in 2009 that talked about conspiracy theories and the Illumanati, you know, that kind of stuff. I'm always putting music up on my Soundcloud page.

You released an acoustic album called Ghetto Folk a few years back.

What had happened was I got into an altercation with someone who tried to rob me and I got my pinky finger severed. I had to have it sewn back. It was crazy. What made the situation even worse was that my van was robbed during that time and I had all of my musical equipment in there. So I had to start again in 2009 and all I had was an acoustic guitar. But the good thing that came out of it was that I wrote the Ghetto Folk album on that guitar. It's got hip-hop beats with a folky thing, and it's really different. I have a new reggae album that I recently finished that isn't out yet, but I'm really happy with it.

[At this point in the conversation, Israel casually mentions that he's working on a new musical project with H.R.]

I'm friends with H.R. and we're going to be working on a new record together. I started by asking him what kind of music he wanted to do. I told him that I had been working on a lot of punk stuff, but he said, "No, I want to do reggae." So I started writing ideas and adding my vocals to them so I could give them to H.R. so he could sing over them and write new material himself.

It's coming full circle for you. That's really great. It was a pleasure speaking with you today.

Thank you, Carlos. I wish I could have learned more about you. Call me anytime and let's hang.

***

Head to Ras Israel Joseph I's Soundcloud page to listen to more of his recent music.

Tagged: bad brains, hardcore, interview, punk