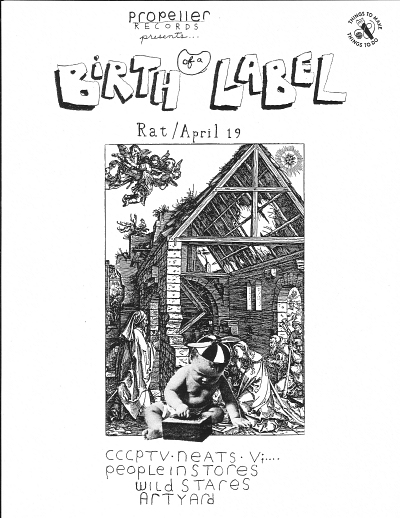

In 1981 a group of musicians based primarily in Allston, Massachusets formed Propeller Records to independently release their post-punk explorations. With a strong DIY ethos informed by Dischord and Crass Records, the Propeller bands shared bills with Boston’s burgeoning hardcore acts at the Gallery East and other local haunts but the label’s output has remained out of print and largely undocumented, obscuring an essential part of Boston underground history.

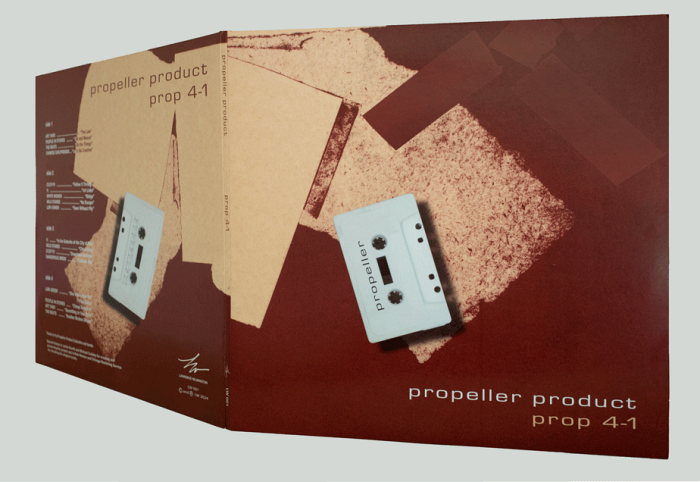

One of Propeller’s most coveted releases is a cassette compilation titled Propeller Product Prop 4-1 (1981), which showcased the diverse sounds of the squad’s angular and inventive musician spaces. Due to a manufacturing error, the original tapes rendered the tunes largely inaudible and further cast the recording into obscurity.

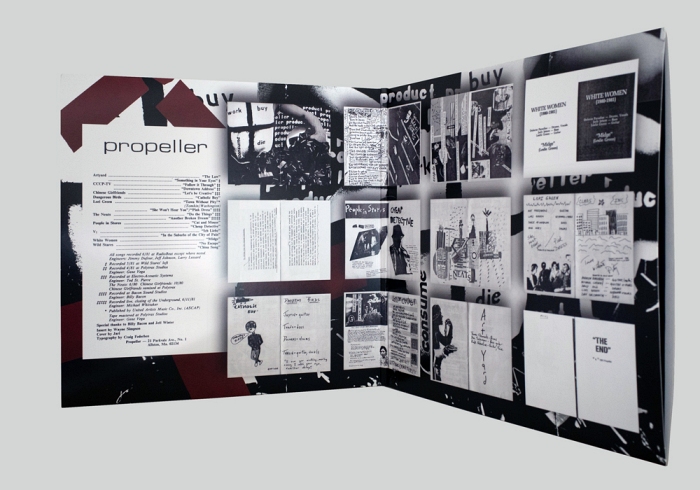

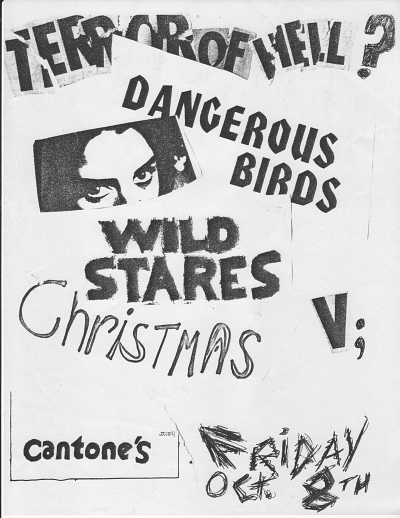

Over time, digital reproductions of the tracks surfaced online but due to the efforts of new Brooklyn-based label Lawrence Wilmington (Founded by Brian Gemmp of Record Grouch in Greenpoint, Brooklyn and Anthony Pappalardo of Ten Yard Fight and In My Eyes), the compilation has been remastered by Bob Weston (Volcano Suns, Shellac, and Chicago Mastering Service) and given a 2xLP 180-gram vinyl gatefold treatment available now with artwork culled from the cassette’s original booklet.

No Echo caught up with Justin Burrill, one of Propeller and Wild Stares’ founding members to look back at early-'80s Boston, the origins of the label, and the gentle rifts between SS Decontrol and the Prop Crew.

Can you tell us about Propeller’s original ethos as well as the underground landscape in the early '80s?

(Justin Burrill): Coming out of the late 1970s punk, there was a swirl of DIY spirit. There were several independent labels, most of them were based around one person or a record shop or club. There were some examples of collectives and cooperatives, mostly in the UK and Europe.

We were a group of musicians who wanted to put out records but had no money and little expertise. We recognized that if we each tried to release things on our own, it would be difficult to get attention from the radio and press, and securing distribution would be very difficult. We reasoned, correctly, that if there was the appearance of a label we would have some standing.

As an interface with the music world, the collective worked the way we had hoped. We were not one hundred percent naive in our expectations for the internal workings. Things did get done, but it was often painful. We would have meetings every week or so at the Parkvale apartment I shared with a couple of other Propeller people, with as many as thirty people there.

People would volunteer for tasks, tasks would have to be reassigned, and there would be protracted discussions (arguments) over artwork for the multi-band joint releases. I sort of wound up as the nominal “head,” because I had worked in record stores and had been laid off from my job so I had some time on my hands.

Zooming in, what was your experience in living in Boston during that time?

JB: Boston was an exciting place to be at that time. The city had a gritty energy and cool spaces were cheap. There was great music everywhere. There was the proto-punk scene, punk, post-punk and hardcore. The jazz, reggae, and classical folks were all on the top of their game, too.

Something is interesting about the dichotomy of Boston as a college town. It has deep colonial roots as well as a transient town that reinvents itself every fall due to the spike in population because of all the colleges. Did you feel that dynamic impacted the music scene of the ‘80s?

JB: I think that the colleges probably do have a lot to do with it in several different ways. You have 200,000-plus young people looking for new experiences, for starters. I think the energy of the Boston scene itself attracts a lot of people who want to make music.

Boston has always had great clubs and the college radio was the best anywhere. I don’t know the Boston scene that well now, but it does seem that it continues to be vibrant. There is always interesting stuff coming out of Boston.

What role did Allston play for artists, musicians, and students, Propeller specifically? Role of BU and Harvard – it felt that there was something academic about Propeller but balanced by a rawness/realness.

JB: Allston, being a student ghetto at the time, featured affordable rents, so it attracted musicians. Many were already there, being either college students or recent dropouts. Most of the Propeller people were people who came to Boston as students and dropped out. B.U., by its very existence, created the Allston phenomenon.

Pretty much all of the musicians lived in Allston or Central Square with a few in Downtown and Jamaica Plain. There were always parties in Allston. Several bands had houses where they could rehearse. People were always changing apartments and bands.

Design is what immediately drew us to Propeller. It almost felt like a cousin to Factory Records. Can you discuss the overall aesthetics as well as the Prop Cassette and booklet?

JB: We drew a lot of inspiration from Factory. We loved their strong, elegant graphics and packaging. We thought it was important to make a similarly distinctive statement with our packaging. Propeller was, in large part, made up of artists and graphic designers. Everyone had very strong opinions on design and aesthetics.

For the cassette booklet, we decided to have each band do their pages, which seemed like a no-brainer, given the collective nature of the label. The cover and the cassette J card were, of course, a different story. I don’t recall the details of the protracted debate, but I do remember that at the absolute last minute, Wayne Simpson arrived with the J card graphic.

Can you speak to the diversity of sound on the tape?

JB: One of the things that bound the Propeller people together was the desire to hear new things.

The musicians were all fans of another’s bands and became friends from going to shows. There was no guiding aesthetic. Everyone was excited to hear people doing something different than what they were doing. Also, the Boston scene then was very male-dominated. Propeller was part of the change.

Can you discuss The Bands That Could Be God Compilation and Homestead in relation to Propeller?

JB: While there was no direct relationship, there are many tangential connections. In addition to Christmas, there are several Propeller musicians included in the bands on the LP. Bands That Could Be God, like Propeller Cassette, were largely recorded at Jimmy Dufour’s Radiobeat studio.

It is hard to know where to start with Gerard Cosloy, I remember him as a kid with a great fanzine. He wrote about Propeller early on in the Conflict fanzine before releasing Bands That Could Be God and moving on to Homestead and signing so many of my favorite bands.

* V; and Susan Anway ... SA was a generation or more older (born in 1951!), what does JB remember about SA before and w/ V; ... then the relationship between SA and the Magnetic Fields

I first met Susan when she was with V: V: were amazing. They started as almost a No-Wave band, but quickly developed into a massive, powerful sounding band. The rhythm section was great, the guitar interplay between Gary and George was really cool and Susan was amazing. She was a punk rock Valkyrie. She was a great singer with an astounding voice. She was also a wonderful human being, may she rest in peace.

Unfortunately, they broke up while recording for the So! EP. I was hanging out in the studio with them as it was happening.

Stephin Merritt of Magnetic Fields would go to Wild Stares shows and probably other Propeller shows and was a friend. Steve or Fran from the Wild Stares recommended Susan to Stephin. Steve Gregoropoulos and he have remained friends over the years. The song "Babies Falling" on the first Magnetic Fields album is a Wild Stares cover.

Any memories of Thalia Zedek’s arrival in Boston?

JB: I first met Thalia when she was playing with White Women. She was very young. You could immediately see that she was special. She had and still has an insatiable curiosity. Around the time she left White Women, she moved into the Parkvale apartment that was Propeller HQ. We have been friends ever since. I played on her Propeller Cassette song that is billed as Dangerous Birds before the actual group was assembled.

Can you talk about the dynamic between the nascent hardcore scene and the Propeller scene?

JB: Propeller had the slightest of headstarts on the Boston Hardcore scene and both were part of punk's second wave which was not to be confused with “New Wave.”

Many of the Propeller people, including me, dug the hardcore bands. In the case of SSD the feeling was not necessarily reciprocal. I love SSD and I like Al, but Propeller and the Wild Stares specifically seem to be a burr in his boot. I recall a thread about the closing of the Rat where he managed to work in a dig on the Wild Stares in his comment.

Boston has a legendary music scene that spans several genres and styles, however, it felt as if things went from pub-rock/proto-new wave right into hardcore and post-punk but punk rock was almost skipped. In a sense, Propeller’s sound was more punk than post-punk…

JB: I think you are right, Boston did sort of skip over “Punk.” My thinking would be that the pub rock/proto-punk bands sort of covered that territory because most of them were very edgy live. Bands like the Real Kids and Nervous Eaters.

DMZ probably should be considered a punk band but they self-styled as a Stooges-esque proto-punk band. There was a New Wave scene, but by ‘79/’80 you had Mission of Burma, Propeller, and a bunch of other post-punk and hardcore bands and hardcore. New York was a bit of the same story. Besides the Ramones, who are the actual NYC punk bands?

***

The 2-LP vinyl version of Propeller Product Prop 4-1 is available for pre-order via Record Grouch.