Past Forward # 2 celebrates Washington, DC's Fire Party and their 1989 album, New Orleans Opera.

A firing party is a military detachment detailed to fire a salute at a funeral. The band Fire Party wasn’t aware of this British term at the time of their creation but their name beautifully symbolizes the end of a male dominant music scene. Washington’s punk subculture by the mid ‘80s had become violent and was in need of a transition into something more thoughtful, politically aware, and inclusive.

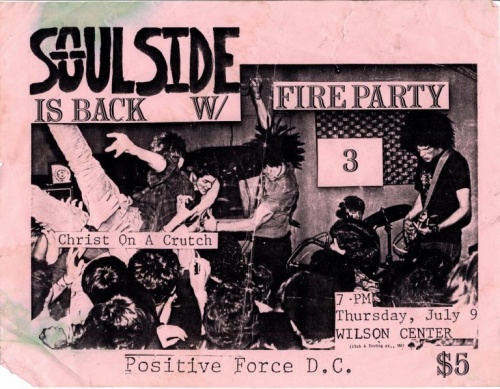

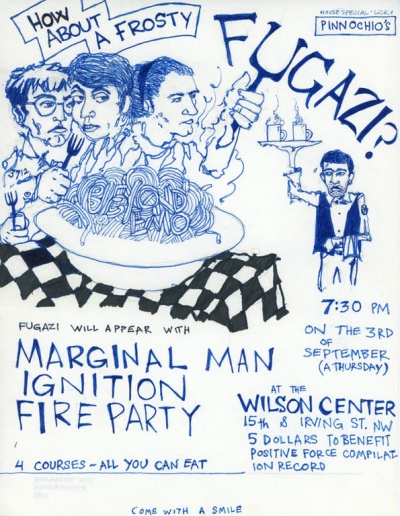

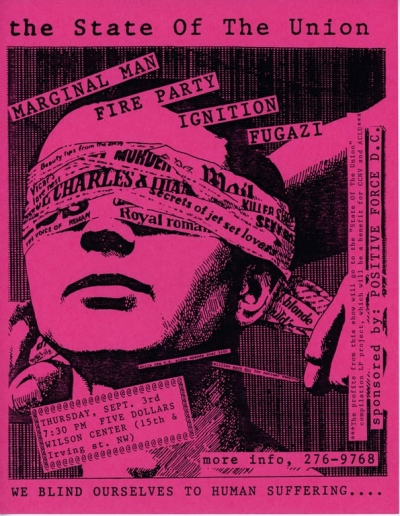

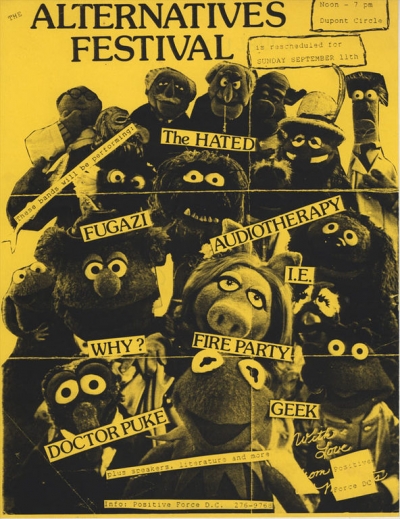

The activist organization Positive Force began creating change by engaging with bands like Rites of Spring, Gray Matter, and Beefeater to help promote their message (social transformation via youth empowerment) that brought about the “Revolution Summer” of 1985. A creative socio-political seismic shift began taking place at this time and Fire Party was born from this movement. The band was a poignant exclamation point at the end of a collapsed boy’s club by 1987. If Rites of Spring was the call, Fire Party was the response.

"Possibility". That was the word Mary Timony (EX HEX, Wild Flag, Helium, Autoclave) recently used in an interview for the music podcast Turned Out a Punk that Damian Abraham of Fucked Up hosts. Timony was talking about growing up in Washington, DC in the '80s and when asked about what she experienced firsthand, Fire Party was the band that delivered something beyond music – the band gave her POSSIBILITY. The word possibility means something so much bigger than inspiration or influence.

Possibility means Fire Party planted the all-important seed that in a mostly male dominated music scene of harDCore, there was a place for women.

The '80s were filled with iconic women in popular music (Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, Grace Jones) but these stars looked like manufactured products an average teen girl could not possibly recreate. Teens also live in the bubble world of their parents so the ability for girls to find other girls playing in bands anywhere near where they grew up was like chasing the impossible dream before the internet. Fire Party was Rock’s answer to the statue of liberty welcoming girls of all color to a promised land where equal opportunity awaited us.

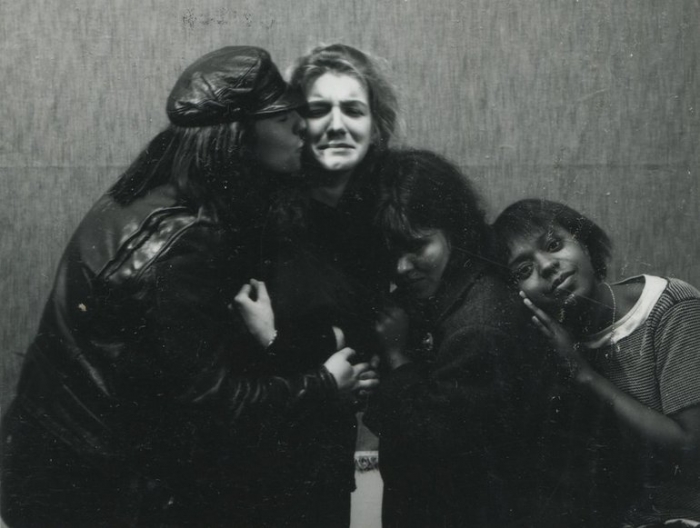

Outsiders viewing Fire Party saw four young women that looked like any one of our friends; accessible, genuine, and real. Many women were (and still are) trying to use sex to sell their music and this was not the kind of band Fire Party was. Their music didn’t have an ulterior motive of trying to succeed for the sake of fame. Following in the tradition of so many Dischord Records’ bands before them, they dismissed that plastic, commercial shine. Their songs carried a feeling of immediacy that captured a dynamic chemistry without the filter of fashion stylists and studio trickery.

New Orleans Opera was produced by Ted Nicely at Inner Ear Studios, a one-two punch that helped to created that distinctive, familiar Dischord essence. Post-hardcore had evolved out of the demise of local bands like Minor Threat and Fire Party helped to advance this emotive, new genre. The only thing that separated Fire Party’s sophisticated melodic tension from the rest of their label mates is that they just happened to be women. Their confident, controlled rage not only ran to parallel to the music coming out of their hometown but was on par with the bruising dynamic range of mid-west bands of that time Die Kreuzen and Naked Raygun.

Bands like Fugazi became masters of listening, responding, and reacting as a machine-like unit but this mature writing technique is blueprinted on New Orleans Opera first.

I know why my DC music loving peers didn’t all race out to buy New Orleans Opera and it wasn’t because their songs weren’t worthy of taking up real estate on their record shelves. I worked in a record store at this time and saw it firsthand. The same people who complained Fire Party weren’t heavy enough, were too pop, or were too different from the other DC bands used these excuses to mask their sexism. The reality is that years before the debut of Fire Party, the mold of harDCore had already been smashed. Rites of Spring and Embrace had pulled the mask off of their rage and were unabashedly sharing the emotions behind their anger. Beefeater was wildly experimental, bringing in funk and multiple other genres to redefine what heavy sounded like with help of audacious lyrics. Scream wrote polished gems making the band arguably the most mainstream sounding one on the label.

Dag Nasty snuck in acoustic guitars to their sensitive pop punk party. Shudder to Think was practically yodeling abstract poetry. In short, Dischord bands had taken a sharp turn away from blistering hardcore. When people say they couldn’t get into Fire Party what they actually mean is they treated gender like a music genre and they didn’t like bands with women in them. This bias is why so many girls are still intimidated to pursue playing in a band to this day. The irony is that for many female musicians, gender is the last thing they want the focus to be on.

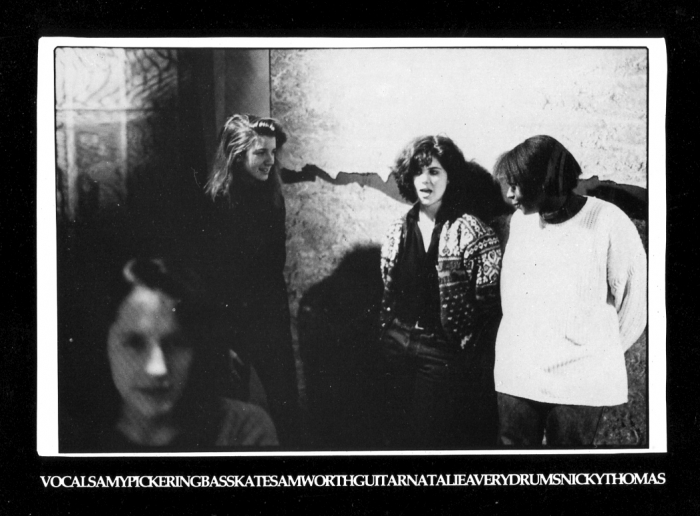

The Riot Grrrl movement that followed Fire Party a few years later would put grrrls, gender identity and feminist politics to the front but for Fire Party, the opposite was true. Gender was a footnote. As different as these philosophical approaches to making music are, the story of Riot Grrrl cannot not be told without a nod to Fire Party: Amy Pickering (singer and mother of “Revolution Summer”), Nicky Thomas (drummer), Natalie Avery (guitar), and Kate Samworth (bass) for helping to cut the path first.

Washington, DC may be the heart of our nation’s governing body but it has been so much more than a political capital; it represents possibility, inclusivity, and ingenuity. The city embraced the self-proclaimed nickname of “Chocolate City” when it’s African American population peaked to over 70% in the city by the 1970s — the largest black city population in America. In 1968 the city struggled to recover from devastating riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King and white flight followed. Families fled to the suburbs and businesses city side were shuttered. There was an unemployment epidemic and a homelessness crisis by the late ‘70s. Shortly thereafter the crack cocaine epidemic created deadly drug dealing turf wars. The city had a somber new nickname, the murder capital of the United States.

This was an unsettling time for the city and that tension poured out of its communities in the form of music unique to this region only. For the black community, go-go (a bass and percussion heavy funk born from Latin African heritage) flourished and for the youth movement, it was harDCore. From these hardships came vast opportunities for those who remained inside the city limits and had a willingness to create. A “do it yourself” attitude was born from necessity and has remained a trademark of this city for over a century; starting with the 5 million newly freed slaves that fled to the city from the south to start new lives after the civil war.

The following interview conversation with Nicky Thomas, the drummer of Fire Party, prompts me to consider the radical DNA that was passed down like an Olympic torch from the generations that proceeded them. Fire Party isn’t just a raucous salute marking the demise of a male-dominated musical era , the band made way for the possibility of a revolution, girl style (see Bikini Kill and Bratmobile for details).

What was life like leading up to the year before the band formed?

Nicky Thomas: I was only 17 when the band got together, but I had been attending shows mostly with my older brother for about four years by then. Before Fire Party, I played in a few bands that played only one or two shows each. I went to the very first Positive Force meeting and many of the early meetings, but when I think back to that time the thing that strikes me the most is just how young I was. I was involved with helping to organize the first PF show at Dupont Circle with Beefeater and other bands. There, I met Tomas Squip who would introduce me to a lot folks and eventually I met Amy. Guy Picciotto introduced me to Natalie on a Friday night at dc space and if I remember correctly we played together a few days later.

What was your AH-HA moment when you knew that the underground music scene was something you wanted to be a part of?

Nicky Thomas: I remember looking at and listening to my brother’s records and Minor Threat in particular. I was so intrigued by the lyric sheet hanging on the wall in his room. After going to my first show I was hooked but I never would have imagined then that the experience of punk and the DC scene would have such a lasting impact on my life. Those earlier shows that I went to were all guys playing - Government Issue, Void, Scream, Marginal Man, Black Flag, Circle Jerks and the usual suspects… I saw Toni Young once with Dove and the Nike Chix many times and that flicked on a switch in my mind.

What do you think it is about the DC environment in the ‘80s that enabled so many young people to do things for themselves and build a small creative epicenter?

Nicky Thomas: It’s hard to pinpoint it but I think it’s a result of a penumbra of factors — DC as a single industry government town where downtown emptied out at night which created space for noise, creativity and exploration; it was Chocolate City with a strong African American community; there were a few seminal people and places that inspired everyone to feel as if they could do it too; and so much more. I also think that when a town has a structure as rigid as the government holding the city down there are bound to be cracks and crevices that creates tension and friction where artist can rub up against that rigidity to create and thrive.

Did any of you have professional music training be it through school lessons, private lessons, family members, or a church? I ask because I am still trying to wrap my head around your debut EP that was as mature and fully formed as it was. There is nothing shaky new band about it.

Nicky Thomas: Amy had some vocal training and I was a band geek in junior high school. I dabbled in everything from flute to bassoon, but one day when our music teacher was yelling a rhythm at the percussion section I remember thinking “come on guys get it together, I can do that beat!” I then had a basement band with neighborhood friends where I was attempting to play guitar. I’m a lefty so I kept flipping the guitar back and forth and was having the hardest time. I was helping the drummer figure out a beat one day and I sat down and just played and was like oh, right, this is what I’m supposed to be playing.

Had any of you appeared on records or stage before Fire Party had formed?

Nicky Thomas: I played a few shows with friends from Positive Force, and then in In Pieces with Ian Svenonius. I had also played some percussion with Beefeater at shows and on their second record. Tomas Squip really encouraged me to believe in myself as a musician.

One of the things that has always impressed me as an outsider looking into the ‘80s DC music scene is how many women were involved both in playing music and behind the scenes. Did it feel like there was a disparaging imbalance back then from standing in the middle of it?

Nicky Thomas: There were certainly a lot of women doing the organizing and behind the scenes work, but when Fire Party was playing there weren’t a ton of women playing in the DC scene all at the same time in critical mass. I would say that while there were a handful of bands like Chalk Circle, the Nike Chix, Broken Siren and Sybil with all-women, but we aren’t all playing contemporaneously. There were also inspiring women in bands like Toni Young and Monica Richards, but the real groundswell of lots of women playing at the same point in the timeline happened with Riot Grrrl.

I know you have been embedded in several music communities across America. How does DC compare in regards to embracing women of color and overall diversity acceptance?

Nicky Thomas: DC was by far the most diverse and accepting punk community that I have been a part of. For sure, it has to do with DC being predominantly African American at the time and having an incredible original underground music style in go-go music happening at the same time as punk. Minor Threat played with Trouble Funk once and Beefeater, Scream and other bands really tapped into a diverse array of influences which really made the scene more approachable. That said, when I walked into my first show which sadly wasn’t Bad Brains, it was definitely predominantly white other than Marginal Man on stage.

Nonetheless, I was drawn to the energy and vitality of the scene that was at first unintelligible to me but it tapped into a deep sense of unbelonging that I had felt since I was a child. Back to the Bad Brains, they were so incredible for me to see as a woman of color and I honestly think if they had been my first punk show my whole life would be different.

Was the start of the band less about feeling the need to express yourselves in music form and more about an extension of a bond and connection between friends who happened to have access to musical instruments?

Nicky Thomas: We started in Natalie’s parent’s basement. Kate, Natalie and Amy knew each other before the band, but when we formed and started playing our friendship bond blossomed. To emphasize again… I was really young and they were a few years older than me, but this bond that we shared shaped my understanding of creating together with others as a vulnerable and intimate act which creates deep connections rather than simply churning out songs. The name of the band came from a time when we stayed up all night talking and laughing by a fireplace. It was a fire party and it solidified our bonds.

Many of you dated people in bands. For years they had the ability to express themselves through music, occasionally airing emotions about relationships for all to hear. Did Fire Party feel like it gave you the opportunity to help balance the male narrative out? (not for feminist agenda reasons but for rather for personal ones)

Nicky Thomas: I sure would like to think that this were true but alas I was a teenager and didn’t even know what a “narrative” beyond story arc was at the time. We were just living it. For me, even the word feminism brought up images of Ms. magazine and white bra-less women marching in ribbed burnt orange turtlenecks. I was a kid so didn’t understand (yet!) how important and central feminism was to what we were doing. I even went to pro-choice marches in DC, and yet I was such a wee thing that I didn’t make the connection between feminist ideology and our actions. I was doing without knowing. Now race, that has impacted me since I was a child so I had more understanding of the way that race functions in this country. But I’m afraid that I wasn’t able to articulate our experience from an intersectional feminist perspective until many, many years after FP.

What was the process like of finding your own voices and songwriting style? It can be so scary in a first band figuring out not just how to play an instrument or sing but how to write a song in the first place no less with three other people, yet when I listen to that debut release, all I hear is fearless.

Nicky Thomas: Thank you. I think that we are living in a time when it’s really easy to just go online and see how something is made or what possibilities exist. It’s really difficult to cultivate that space of not knowing and originality that we had in the 80s. As a result, it is now the norm to chart a path and have a sense of where you are going or what you want your voice or sound to be. When Fire Party formed we didn’t have a plan beyond the immediate — practice and piece together songs that we could play in the way that we knew how to play, play a show, practice, play another show, rinse, repeat.

Everything that we did beyond practicing and playing small shows locally was a pleasant surprise. If you don’t have expectations then you don’t really have fear. Sure, we were nervous before shows, but there was no fear of failure because there was no expectation of success. That freedom allowed us to be authentic to what we could do.

It seemed like Fire Party moved at hyper speed from basement band to defining a strong musical identity to being on an independent record label that literally the whole world was aware of, to then touring both America and Europe. Did it really come together as fast as that?

Nicky Thomas: It was pretty fast. We went to Europe to tour with Scream within the first year of playing shows. But also remember that we were all part of this small scene before we started the band and Dischord was simply our friends Ian and Jeff who put out records to us. Amy also did mail order for many years at Dischord. It was small and connected to what we were already a part of so everything was within reach, and at the time didn’t seem to be that big of a deal.

Was the band at the time received as a novelty because you all happen to be women and if so, do you feel like you ever escaped that stigma while the band was active?

Nicky Thomas: There were many attempts to treat us as a novelty but we always resisted that role and really hated being thought of as an “all-girl band” so we downplayed that as much as possible. I think we did a really good job at attempting to escape it, but sometimes I wonder how things would have turned out if we embraced it and owned the narrative like the riot grrrls did a few years later.

Which bands (local or touring) did you feel like Fire Party had the deepest connection to musically at the time?

Nicky Thomas: Locally, we loved playing with all of our friends’ bands even though we weren’t always musically similar. Our deepest connections from playing shows and touring were with Scream, Fidelity Jones, King Face, Soulside and Fugazi and so many more bands - the usual contemporary DC suspects. We toured for a few days with That Petrol Emotion in Scotland which we all loved. We love a wide variety of bands - Wire, the Obsessed, Nirvana (pre-Dave), The Slits, The Damned, The Church - this is a random grouping - and really so much more. We all loved music and listened to everything that we could get our hands on. Natalie worked at Yesterday and Today Records, and Kate and I worked at Olsson’s Books and Records which speaks to the centrality of music in our lives.

Fire Party toured overseas a few times. How did that come about for such a new band at the time and was the public response to the band different over there verse America?

Nicky Thomas: We went with our ‘big brothers’ in Scream the first time and that really gave us a boost over there. They were so loved in Europe that I honestly think they could have brought over just about any band to open for them and the audiences would have responded positively. People were so open-minded and supportive of us in Europe. We played so many shows in Germany and the Netherlands that it really felt like a second home.

How did the songwriting and recording of New Orleans Opera evolve from your debut release when the two records only came out a year apart? Considering the band’s growth between the two records, I get the sense you were practicing and playing a lot between those two recording sessions.

Nicky Thomas: The growth came from going on tour with Scream in Europe. Watching them every night for 3 months and playing, as well, put our growth on overdrive. I was a completely different drummer after watching Dave Grohl for 3 months! I often say that he was my first and only drum teacher!

What does the name of the record New Orleans Opera reference?

Nicky Thomas: We had a magical time in New Orleans once. Everything from staying at a motel where the desk attendant said “good luck, girls” as he handed us our keys from behind a bulletproof glass to meeting a photographer on the street who wanted to take our picture because he could tell that we were up to something interesting. We remained friends with that photographer for decades and one of the photos on the cover was taken by him. We were really moved by the serendipity of our time there, even if it was only for a few nights. Thinking back on it I think that we were so lucky to be travelling without phones and the constant ability to capture and review moments. We got to be present and open to possibility.

How was the record received at the time in the press? (I struggled to find old reviews in zine archives or on line) I can’t imagine the complicated baggage that comes with being on label like Dischord. Some remarkably helpful (well-connected network for touring, a built in fan base, world wide distribution, press attention) but then the lash back of small minded harDCore fans who thought everything on the label should be fast and played by men.

Nicky Thomas: At the time the press was comprised of ‘zines, which were made up of individuals and small groups of friends. Larger media outlets weren’t really covering the music scene with regularity so we weren’t impacted by the media in the way that later bands were. To be sure, there were some boys who didn’t know what to make of us but we kept playing. There was a nice review in the Washington Post once, but I know for me I never put much weight on reviews because I just wanted to play music and be with friends. Being on Dischord from the recording and putting out the record side could not have been more direct, honest and simple, really. No contracts, no b.s. and no disputes to this day. Just friends putting out music.

What brought about the demise of the band?

Nicky Thomas: I think mostly we were simply changing and growing up. We lasted 3 or 4 years which is a long time in your teens and early twenties.

Are any of you still active in music or the arts?

Nicky Thomas: I play with Hard Left and I always have a project going with my dear friend Meghan Adkins — sometimes it’s only in our minds though. We played in Mavis Piggott together in the '90s in Seattle and in Chaos of Birds in the '00s. I also love participating in the artist Chris Duncan’s immersive sound piece called 12 Symbols whenever I can. Also, I’ve been writing a memoir about not only my time in Fire Party but growing up black and punk in America!

Kate is an incredible artist, I mean, seriously incredible. Her page can be found here.

***

Read Tracy Wilson's first installment of Past Forward featuring The Fisticuffs Bluff at this link.

Tagged: fire party, past forward