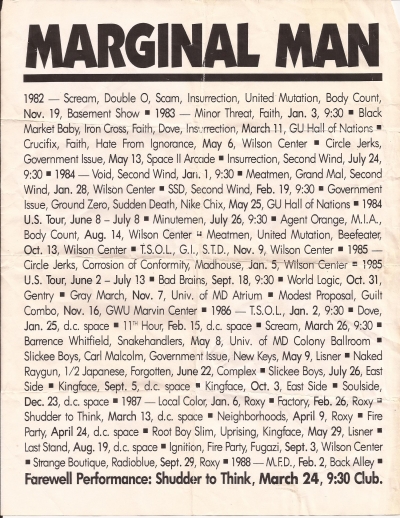

In his latest piece for his A Hardcore Conversation interview series, Anthony Allen Begnal speaks with Kenny Inouye, guitarist for the influential DC band, Marginal Man. —Carlos Ramirez

You are Kenny Inouye, guitar player from Marginal Man, correct?

Yes I am.

What was it like coming from Hawaiʻi and moving to DC or were you actually born in DC?

I was actually born in DC. However, I spent a lot of time in Hawaiʻi when I was growing up, since all my family is in Hawaiʻi.

How did you get into punk and hardcore?

Probably in a way similar to how a lot of folks got into it. I was heavily into skateboarding starting in the Summer of ’75. I was 11 at the time. Skating always had a relationship with hard and heavy music, even back then. Back then, we were the kids listening to Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and KISS, while everyone else at school was listening to Barry Manilow and the Carpenters. As time went on, you couldn’t help but be wanting something different though, since that music, as great as Black Sabbath may be, in a lot of ways was the music of our older siblings and cousins. It wasn’t really “ours."

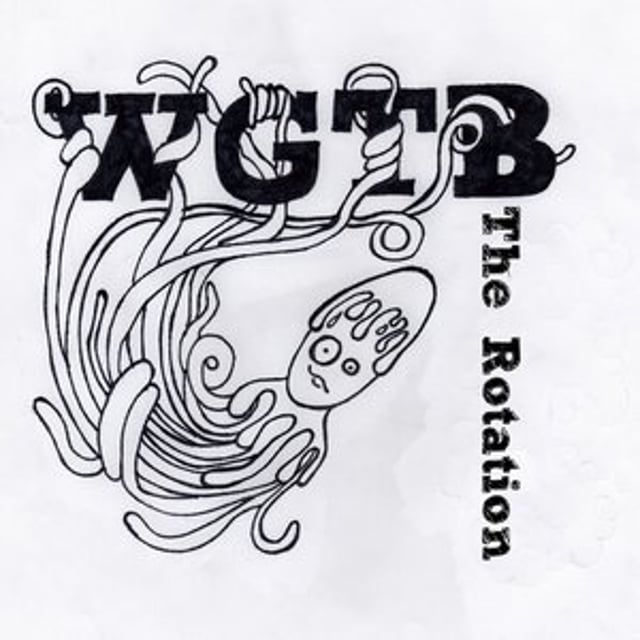

Punk came along at the perfect time. The first time I heard the Sex Pistols was in August 1977 at the Freestyle Skatepark in Gaithersburg, MD. They were playing the "God Save the Queen" single. I remember it clearly because one of the kids at the park had just heard that Elvis had died and he was completely freaking out. The guys who managed the skatepark were playing the Pistols on WGTB, which was the college radio station for Georgetown University. If you look at old DC fanzines from the early '80s, you’ll notice that a lot of folks from the DC hardcore scene cite WGTB as a place where they heard early punk.

As time went on, rock mags like Creem started giving punk a lot of press. Creem was the place I first heard about the Ramones, Blondie, Clash, Damned, Iggy Pop and the Stooges, Richard Hell, Stranglers, Devo, etc. At about the same time, Skateboarder magazine was covering punk, but with a harder, more West Coast focus, and that’s where I first heard about Avengers, X, Dead Kennedys, Germs, Black Flag, Circle Jerks, Adolescents, etc. When you’re a teenager and you’re energetic, frustrated, and into hard and fast music, as soon as you hear music like what all those bands played, that became all you wanted to listen to.

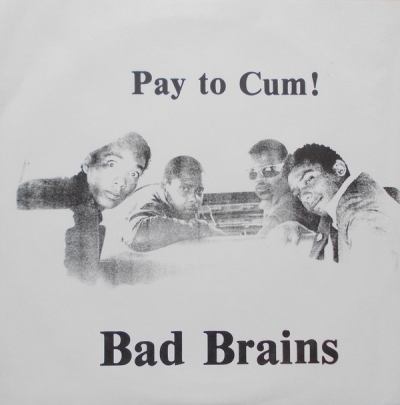

As time went on, I started to discover there was a music scene in DC. I kept hearing about this band the Bad Brains and how amazing they were. I bought their “Pay to Cum” single during the Summer of 1980 at a local record store during my lunch break and was positively blown away by what I was hearing. Everything about that record was different: the sound of the guitars, the sound of the song itself, the blistering pace at which they played, how precise their playing was, and that singer. When I first listened to it, the first thing I thought was that HR sang "Pay to Cum" the way a scatting jazz singer would sing if they were on heavy amphetamines. It was a revelation.

I was hooked. I’d only heard one song and I had to see this band. I ended up listening to both sides of that record over and over for the next hour, studying every aspect of both songs. I couldn’t believe these guys were local. The thought that these guys lived and played in the same area just blew me away. I had to see this band.

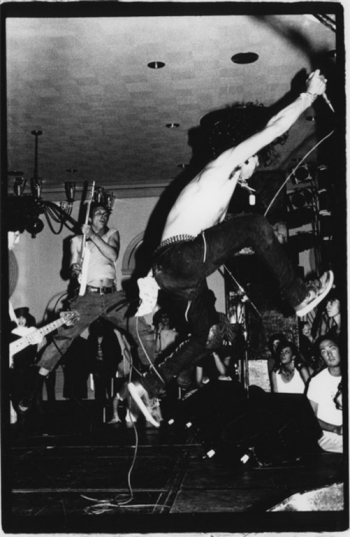

A few months later, November 1980, I saw that the Bad Brains were opening for the Stranglers. The bill was Stranglers, Bad Brains, and Black Market Baby at the Ontario Theater. I kinda liked the Stranglers, and I knew I wanted to see the Bad Brains, so it was a no brainer. In a nutshell, I went to see the Stranglers, but everyone left talking about the local openers. To this day, Black Market Baby was one of the best bands I’ve seen. Their songs were super catchy, well written, and the band had serious chops.

When the Bad Brains hit the stage, it was unlike anything I’d seen at that point, or since. To this day, I’ve never seen a band come on stage the way they did during that period of the band’s history. The lights went down and immediately the crowd roared and started going nuts. The stage lights went up and the band came on stage and the crowd got louder, then HR got in front of the mic stand, raised his arms over his head and yelled “Yeah!” and the crowd went apeshit. They haven’t played a note yet and the crowd was already in a froth. They launched into their first song, I think it was "Attitude," and it was like a bomb went off. I will never forget that gig.

However, the thing that made me want to get involved was what happened after their set. After their set everyone was milling around the lobby of the theater. The thing that struck me was that everyone was involved in something; setting up shows, selling fanzines, playing in bands, etc. I couldn’t just be a spectator. I had to get involved, and that’s pretty much all I thought about or did for years afterward.

How did you start playing guitar to begin with?

I first started playing guitar when I was 12. However, I had to earn my way to playing guitar so my quest to learn guitar started a year earlier, when I was 11. My folks had heard all kinds of stories from their friends about how their kids picked up an instrument for a week, only to never touch it again. My dad was skeptical about my interest and thought I’d be giving it up in a similar fashion. So he made a deal with me. I would learn an instrument that he knew and understood. If I learned it and showed I was serious and could stick with it, he’d help me get a guitar and I could learn guitar.

The only fretted instrument he knew was ukulele, so he bought me an ukulele and set me up with someone to take lessons from. At the time he described him as a “friend of his.” As time went on, I realized that his “friend” was actually pretty well known. Herb Ohta, better known by his stage name, Ohta San, was an internationally acclaimed recording artist. At the time, he was coming off the success of the Song for Anna disc that had sold about 6 million records. He was an amazingly patient teacher all things considered, especially when he knew upfront that I ultimately wanted to play guitar. Also, considering that rock really wasn’t his thing, he was very understanding and did a good job of working with me.

I actually got pretty good at the ukulele, but I still wanted to play guitar. However, one thing he taught me that really stuck was strumming technique. He really drilled into me that everyone focuses on the left hand and what it’s doing on the fretboard, but the right hand is more important. If the right hand isn’t doing things right, nothing sounds good. He really drilled into me the importance of different strums, rhythms, pacing, voicing, etc. That was an invaluable lesson. In an odd way, I really owe the guy for anything I accomplished playing in bands. This is especially true considering the fact that once I got a guitar I never really took lessons or learned how to properly play.

I started taking guitar lessons through the local recreation department, it was a room of 30 kids all trying to play at the same time. It was terrible. But I broke my arm skating after about 4 lessons, missed the rest of the lessons of the session, and never took another guitar lesson. All the guitar stuff I learned was through playing in bands with friends or figuring it out on my own.

Did your classmates in high school know about your involvement in the hardcore scene?

[Laughs] Yes, and this brought about no cred in school whatsoever. This was during the days that listening to punk rock meant you were made fun of, liking punk rock meant you were harassed, and actually being part of that scene was like declaring yourself an outcast and putting a target on your torso. It was a commitment. You knew that you were making a serious choice and that you were going to be ostracized from that point onward.

You were not in Artificial Peace, so how did you end up meeting the rest of the Marginal Man guys and forming the band?

I’d known those guys from seeing them around at shows. I was really into Artificial Peace and went to pretty much every show they played. As a result, they all kind of knew me from that. The way I got on their radar as someone who could play guitar came kind of indirectly. I had heard through the DC rumor mill that Pete, Steve, and Mike were thinking of leaving the band and wanted to start something of their own. I also heard they were looking for a bass player. A few weeks later, I was at a party and a guitar was getting passed around, and I was playing. I noticed that they were there, so I handed the guitar to someone else and approached them.

I said, “I know I’m not supposed to know this, but I heard that you might be thinking of starting something new and that you might need a bass player. I just want to let you know I’m interested. I don’t own a bass, but I can play one and I’d be willing to buy one if I could play with you guys.” They were very nice, said thanks, and that was the end of it. A few weeks later, I ran into them at a Social Distortion show (if you ever seen the movie Another State of Mind, that DC show in the movie is the show I’m talking about).

They said that they were putting together something different, something with two guitars, and were wondering if I was willing to practice with them. At the time, Chris Stover from Void was playing bass with them. Of course I said yes! I practiced with them, and that was the start of Marginal Man.

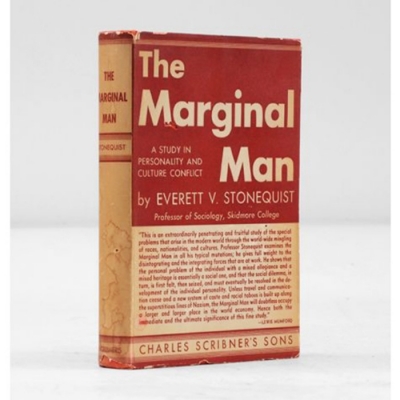

How did you guys get into that whole Marginal Man concept and decide to name your band after it?

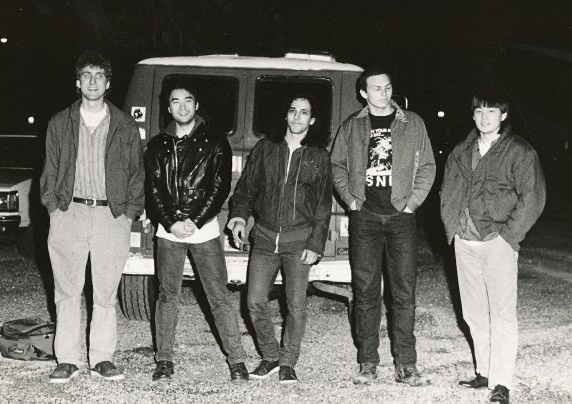

I came up with the name after we’d gotten a few songs under our belt. I was in college and heard the term “marginal man” in a sociology class. The definition, “an individual partially assimilated into two or more different cultures but fully assimilated into none of them," that concept of being “outside looking in," really resonated with all of us. We felt it fit us musically (we didn’t play straight ahead thrash and didn’t want to limit ourselves to any single sound), culturally (the band was multiethnic), and socially (none of us were really the “popular kid” in school or the punk scene).

Did you all talk about what kind of band you wanted to form or was it just like, we wanna form a hardcore band?

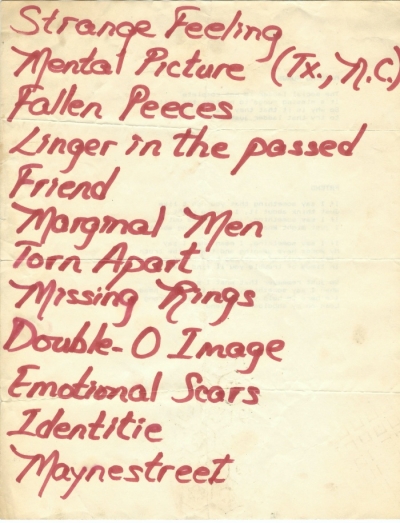

We really only had one conversation about a “sound,” which basically sprang forth from Pete, Steve, and Mike feeling limited by success of Artificial Peace’s sound. While it was great that folks seemed to like what they were playing and that the cuts on Flex Your Head were popular and resonating with a lot of folks, they wanted to be a bit more adventurous. I think it was maybe the third or fourth practice when there was a band meeting and it was decided that if everyone liked a song, no matter what it sounded like, that was going to be part of the set list. That was really very freeing because as much as we liked the fast hardcore, we also liked a lot of other kinds of music.

You were one of, if the not the first hardcore bands to start out with two guitars. At the time, you also had groups like Black Flag, SSD, and Scream around, and Minor Threat added a second guitar player later. What inspired Marginal Man to have two guitarists?

That came out of Steve, Pete, and Mike wanting to do something different. I really have to give those guys a lot of credit because the stuff they had in development when I joined was stuff I immediately gravitated to.

How did you and Pete Murray work out your guitar parts?

There was really no set way that we approached things. It really depended on the song and how things were flowing during practice. It also depended on how the song was developing when the writer shared it with the band. If it was all written, then all the guitar parts were figured out. Other times, someone would come with a song or just a riff, and we’d all build on it at practice.

How did songwriting go in the band? Was there a chief songwriter or songwriting team or did everyone contribute?

Everyone contributed, and everyone in the band has songs to their credit.

Your first record definitely has a pretty strong hard rock/metal influence along with there hardcore, where did that come from?

It’s interesting you say that, since I’ve heard folks characterize it as hard rock, English punk influenced, LA punk, etc. Candidly, it’s a product of what we all were listening to and are into. We all were/are into different kinds of music, so that’s just how it turned out.

You guys moved away from that sound on the subsequent albums, especially on the self-titled record from 1988. What inspired that?

It really wasn’t a conscious decision. Everything we ever did musically was organic. Nothing was calculated. Regarding the third record, looking back on it, I’d be curious to see what a fourth record might have sounded like had we stayed together. I always felt like that third record sounded like a transitional record, and that the record after that would’ve been a really good one. Having said that, one of my favorite songs we ever did is on that third record, “Under a Shadow."

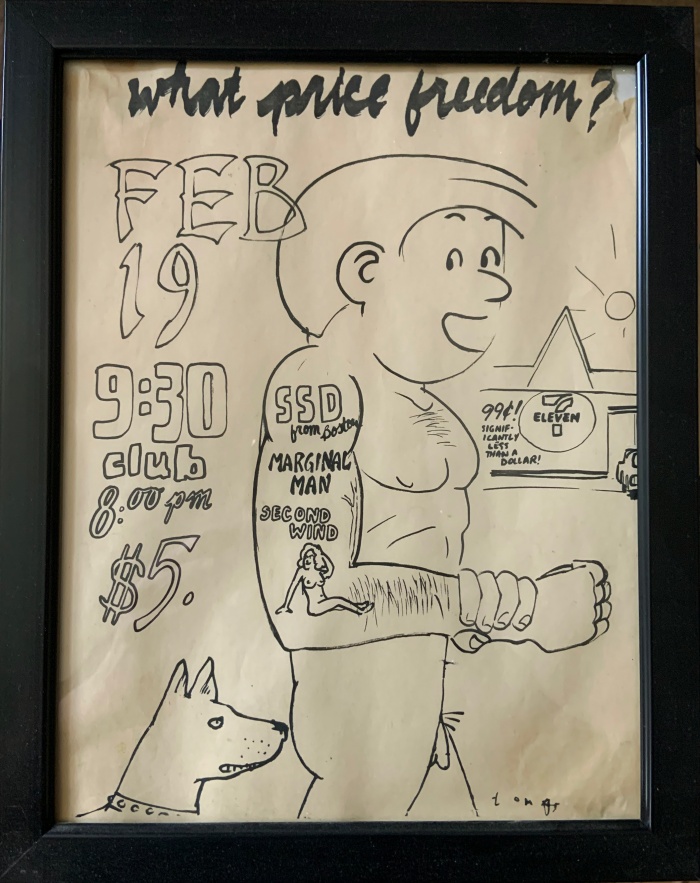

I saw you guys at the OG 9:30 Club in February of 1984 with Second Wind and SSD. What are your memories of that show? And what about that flyer, which is probably one of the strangest hardcore show flyers that I’ve ever seen?

I’ve been wracking my brain trying to think of what that might be, but can't remember. Even did some Google searches, but couldn't find anything.

Here ya go (sends Kenny the flyer)!

[Laughs] Oh, that flyer! Funny story behind that one. Tomas (Beefeater, Red C) did that flyer. We used to hang out a lot at Eric Lagdameo's (Red C, Double O, Dove) house because Andre and I were tight with his younger brother Manolo, plus of course the Red C connection between Eric and Pete Murray since they both were in Red C. Tomas came up with that flyer out of nowhere. We all thought it was pretty hilarious, but as far as I knew it was never actually used to promote the show (i.e., handed out at shows, hung up around town, etc.).

I'm not sure what Tomas' perspective was on making that flyer (after all, who can ever really know what Tomas is thinking), but I seem to recall that he liked the juxtaposition of the guy from the Family Circle comic strip looking buff with these bands tattooed on his arm, not to mention being nude. I'm kind of laughing uncontrollably as I think about this, actually. My guess on the inclusion of 7-11 is that I believe at the time he was living at Dischord House and those guys (Ian, Jeff, Sab, etc) kind of lived off of 7-11 food for a while because there was a 7-11 across the street from Dischord.

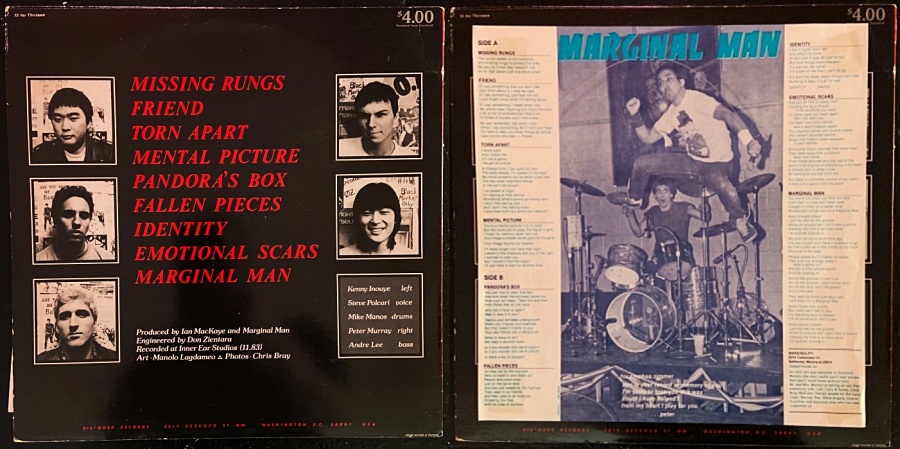

Ah, ok now we know! And I in fact grabbed that off the wall in the 9:30 Club hallway so they were hung up at least a little. Who did the band’s artwork and where did the ideas come from?

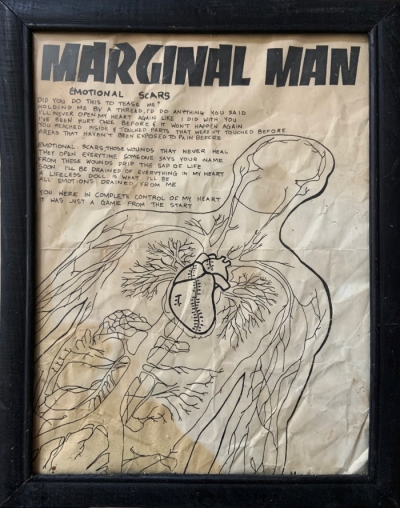

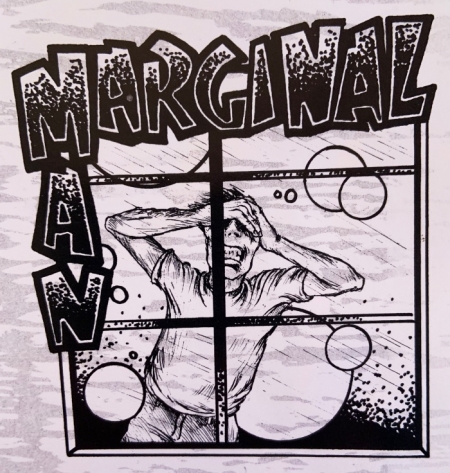

A number of people did the artwork for the band. The cover of Identity was done by Manolo, our roadie at the time. After that, Rachel Sengers, a friend of the band, did a lot of our artwork. All the stuff that has a manga/anime look to it was done by her. As far as the ideas, they came from everyone. Also, everyone in the band did some kind of artwork at some point in the form of flyers.

I also remember you guys used to hand out flyers just with the band name and artwork, not advertising a show or anything, who’s idea was that?

That was Manolo’s idea, and it stuck throughout the band’s history. The idea was to sort of establish a vibe, look and identity to the band early on. Plus, most of those early flyers had song lyrics on them, which helped folks in town get a sense of what we were about lyrically before we had a record out. It also made it more likely that folks would sing along at shows before we had a record out. Back then you really had to think outside the box as far as how you’d get your message out. Everyone was learning as they went along.

There was a definite emotional side to a lot of the band’s songs. Where did that come from and do you feel little bit responsible for, or a kinship to some of the “emo-core” bands that followed after you guys?

The emotional edge to the songs wasn’t a deliberate thing. As I mentioned earlier, the only rule to the band was that we would write about what mattered to us at the moment, and if the rest of the band was into it, it became part of the set. That really was an incredibly freeing approach to making music.

As far as the emo-core bands, I can’t really say we feel “responsible” for them or a kinship. From where I sit, it seems like they were just coming along and doing their own thing.

Your father, Daniel Inouye, was, of course, a US senator and WWII hero. What did he think of the whole punk rock and hardcore thing? And your involvement in it in particular?

He kind of had two minds about it. On one hand, he was really into the fact that I was into music, creating music, and having some level of recognition from it. He was a musician himself, playing saxophone, clarinet, drums, and ukulele. He used to have a band when he was in high school and they’d play big band music like Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, etc. He’s actually the guy who got me interested in music and gave me one of my first albums, the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. On the other hand, I think like a lot of parents I think he occasionally wished I was doing something more “normal” and conventionally career oriented.

Did your parents ever see Marginal Man live?

He and my mom saw us live several times. He saw us twice at the old 9:30 Club and both of them saw us play University of Maryland. I will say that I remember that when we played Lisner Auditorium for the first time that they both kind of realized that the band was a real thing and not some kind of hobby. They knew what Lisner Auditorium was and as a result, could relate to it. We actually played there twice, both benefit shows, both of which sold out. One was a Rock Against Hunger show, the other Rock Against Apartheid.

As a bit of background, Lisner Auditorium is part of the George Washington University Campus and is on the National Register of Historic Places. It was considered to be the focal point of culture in the Washington DC area until the Kennedy Center was built. It’s also what most folks would consider a “nice” place, not a punk rock hall. As a frame of reference, when Steven Colbert interviewed President Obama, it was at Lisner Auditorium. Once we played there, they could no longer tag us as only playing places they’d never heard of.

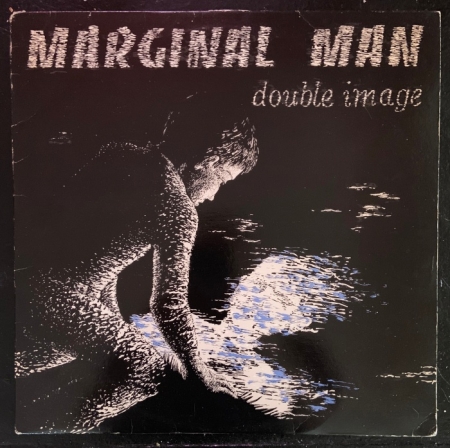

After Identity, Marginal Man left Dischord for Gasatanka/Enigma on your second record, Double Image. Why/how’d that happen?

Identity came out a few months before we went on our first US tour. By the time we were on the road, we’d already written more than half of what was to become the Double Image LP, and by the time the tour was done we were well on the way to having the entire disc written. We were really beginning to gel as a unit and we were really excited to get into the studio, record the next record, and go on the road again to support that record.

Pretty much as soon as we got back we met with Ian [MacKaye] and Jeff [Nelson] at Dischord to talk about putting out another record because we were really stoked about how the songs were developing and we wanted to have a record ready so we could book another tour. However, when we met with them, they weren’t interested, and we were really disappointed. I still remember the van ride back to the practice space, and everyone being really bummed out. The question became, “What do we do now?”

Now, this is a good lesson and example of how much you learn as you’re growing up and how you’d handle things differently if you knew then what you learn later in life. For example, if this had happened when I was a few years older, I wouldn’t have just thought “Wow, they don’t want to do it, I guess we’re out of luck.” I would have started asking more questions about why they weren’t interested. Was it the music, was it something about us as a band, or was it something going on with them? Or any number of other questions. You learn later in life not to just take no for an answer, you at least try to figure out where that “no” is coming from. Looking back on it, they were probably strapped for cash and couldn’t contemplate putting something out as a result.

Given that we had material we were really enthusiastic about, we really wanted to get into the studio and put out another record and tour, so we started thinking about looking at other labels putting the disc out. If Dischord changed their mind, we would’ve been very happy to put it out on Dischord. But if someone says they’re not interested in putting out your music, you kind of have to think about what your other options are. You’re not going to say, “OK, well I guess nobody will put our stuff out, so I guess we’ll just give up.” You focus on how you’re going to get the music to people and how you’re going to get on the road again. Eventually, Gasatanka/Enigma showed interest, which is how we hooked up with them.

Brian Baker of Minor Threat fame is credited for “Production” on the Double Image LP. What did he bring to the table for that record?

Brutal honesty. Brian’s the kind of guy where if he thinks something isn’t good, he’ll tell you and he’ll make sure you know why he feels that way. He made a lot of really good points and helped make the record better than it would have been otherwise. Plus, we all knew him and felt good about working with him.

So, what’s 70% of 0 (which is what it says on the inner groove of that record)?

70% of 0 is Pizza. That came from a show we did in Denver on our first tour. The promoter messed up somehow, I think it was something like he had to move the show to a different venue and didn’t advertise the change, or something like that. As a result, hardly anybody showed up. As it turned out, there were only four or five people or so who showed up, and somehow nobody ended up paying to get in. At any rate, the deal was that we were to take 70% of the door. Two of them were drunks who just wandered in off the street and didn’t know who we were. Since they didn’t collect any money at the door, the promoter couldn’t pay us, so he offered us a pizza. “70% of 0 equals pizza.” It turned into more of a jam session than a gig, with folks yelling out song names and us trying to play them. We did a lot of Hendrix and Led Zeppelin covers at that show.

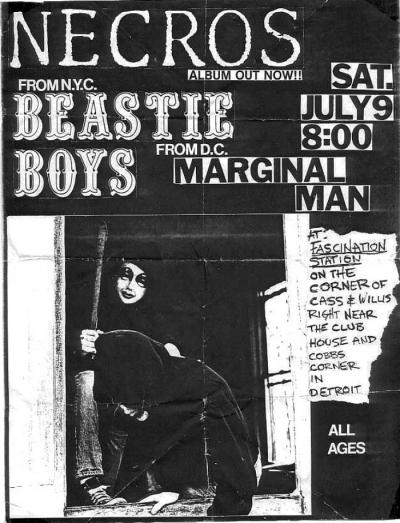

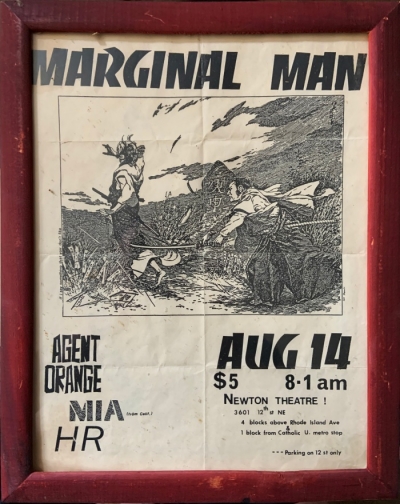

You guys played shows with a wide variety of punk and hardcore bands of the day, such as Circle Jerks, TSOL, Necros, Beastie Boys, COC, Meatmen, Crucifix and many more. Some of those seem like pretty disparate bills, do you have any favorites that you particularly liked playing with?

I really dug playing on all those bills, although we never ended up playing with the Beastie Boys. They were on the bill for a show we played in Detroit, but they never made it. I think it was because their van broke down or something. I was a fan of all the bands you listed, so playing with all of them was a way for me to see a band I liked. Having said that, I will also say that Necros and COC were so helpful to us early on. Necros gave us our first show in Detroit, and COC booked us to play our first show in North Carolina. Both bands were so helpful to bands who were starting out. They really epitomized how bands would help each other out back in those days.

And we played with the Circle Jerks a lot, several times in DC and at least once in Trenton. We were fans of TSOL and they were good guys to us as well. We played with TSOL in NYC, DC, and I think Trenton as well. Plus, when we played LA, we stayed at Mitch Dean’s place when he was drumming for TSOL.

What was touring like for you guys? Did you have roadies or was it just the band on the road? Did Dischord float you guys any tour support money?

Touring was definitely low budget and DIY. On our first tour, we had a roadie come along with us (Manolo, the only roadie you’ll ever salute). On the second tour, it was just the band. As far as “tour support,” Dischord gave us copies of the Identity disc to sell while we were on the road, which really helped a lot.

Your third, self-titled album came out posthumously on Giant Records and sounded a bit different than the other two. What’s the story there?

It’s funny you ask about that disc. Looking back on it, I look at that disc as a transition disc. We were all into different stuff at that point, so writing became more of an individual thing, rather than a group thing like it was for the previous records. I’ve always believed that if the band had stayed together, that the next disc would’ve been really great. That self-titled disc has some of my favorite songs on it, especially “Under a Shadow."

How did the band ultimately break up?

Looking back on it, it’s kind of an odd story. I was actually the one who got the ball moving on the band breaking up. We had just finished practice and were hanging around and talking. Next thing I know, I’m talking about how I wasn’t having as much fun being in the band as before, and then the others starting talking and saying the same kind of thing. At this point, we’d kind of hit a plateau. We had no problem getting booked and playing shows, and we had a loyal fan base. We could’ve easily kept going, going up and down the east coast and Midwest, heading out west every now and then, and playing the same places over and over. However, that somehow didn’t feel right.

You never want to be that band that folks say, “Wow, they’re still together?” or worse yet “Man, they should’ve quit a long time ago.” We had an audience that was loyal and also made it clear to us how much the band meant to them. To this day, I still get email from folks who tell me how much the band meant to them and how the songs helped them through some really tough times. When you have an audience like that, you realize that you have a responsibility to them. They believe in you, and you are where you are because of them. You have a responsibility to never forget that and always keep it real and meaningful.

So, we decided to go out on top, on our own terms. The funny thing was that while we were playing out of town constantly, and were playing DC very regularly, we hadn’t played at 9:30 Club in a little over two years. The person at that point who was in charge of booking local bands into the club had convinced the owner that we weren’t worth booking and that we didn’t have an audience. As it turned out, a new booking manager had been hired, and she didn’t know anything about the band, which worked to our advantage. We called her up, explained we wanted to do a farewell show, that our first show was at 9:30 opening for Minor Threat and Faith, and that we wanted to end our run there, complete the circle, so on and so forth. She did her due diligence, folks told her we would draw a crowd, and she was able to talk the owner into giving us an “off night,” a Thursday night, so that if the nobody shows up it won’t be as much of a problem.

Keep in mind the owner had been told for a couple of years that we didn’t have an audience. A few weeks before the show, she calls us up saying that tickets are selling so fast that she thinks it’s going to sell out and wanted to know if we’d be willing to do a second show that night. We agreed to do two shows and both shows sold out. So, our first show was two sold out shows in one day opening up for Minor Threat and Faith at 9:30 Club, and our farewell show had us headlining two sold out shows in one night.

It was a good way to end it. It was crowd and band together one last time, and it was very vindicating. It reminded us how fortunate we were to have had the band, and we hopefully were able to show our audience how much they meant to us.

What did you do after and do you keep in touch with other former Marginal Man band members?

Oddly enough, about after the band broke up, I ended up becoming the booking manager at the 9:30 Club for a couple of years. One of my best work experiences ever. As far as keeping in touch with the other members, we all keep in touch via email, text, and phone on a fairly regular basis.

What are you currently up to?

At the moment I work at University of Hawaiʻi–West Oʻahu as the assistant to the vice chancellor for administration.

Alright man, thanks a lot, Kenny!

***

Donate a few bucks to help with No Echo's operating costs:

Tagged: a hardcore conversation, marginal man