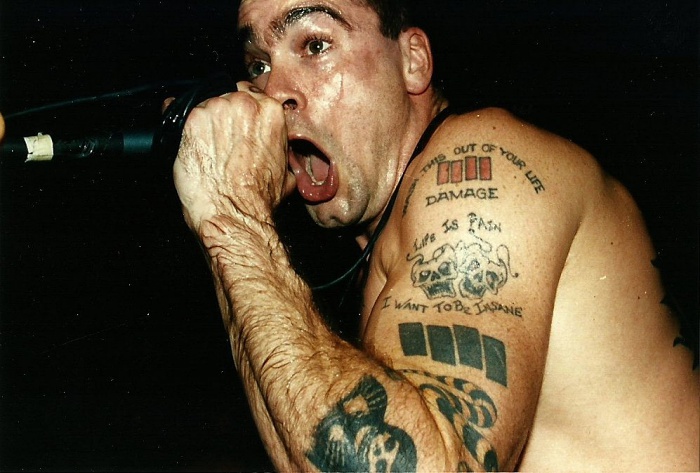

Henry Rollins is my hero.

Which…is a fairly large word, despite its relative lack of letters. Ascribing it to someone who exists in the popular culture–particularly someone who’s name was made independent of political or entirely selfless ventures–can sometimes be difficult as well. We forget our heroes, even the very best of them who we consider to be the ultimate paragons of humanity, are just that–human. Possessed of all the frailty and selfishness that seems born into our species. It can always be dicey when choosing these people–all to often they can fail us in spectacular ways when we place them on these pedestals or project onto them our image of who they are, when invariably they are infinitely more complicated.

Rollins, however, is someone who’s frailty and mistakes he has bared as much as his ferocity and indefatigable nature. And perhaps that is what first endeared me to him before I investigated further and found commonality. Born in my neighborhood in DC and into similar circumstances, attended a competitor highschool of my own, got into punk at the same age, and has poured endless hours into his descriptions of his own alienation and inability to really quite jive with the rest of the world at its same frequency. These were things that I desperately felt when first discovering him, and latching onto this figure who not only came from near identical circumstances but seemed to feel the way I did in the world gave me infinite inspiration to try and mimic his indefatigable nature, to the best of my ability.

Rollins has never let his own frailty or mistakes or even fears dominate him–he has used them as crucibles, as pure fuel for his part-animal, part-machine incredible campaign against life itself. In defiance of time he has created an incredibly deep oeuvre of writing, music, poetry, interviews, radio shows, film appearances, photographs–an amount of work thats sheer amount seems to beggar any notion of the reasonable usage of time. He has done it. And he has done it in spite (or perhaps to spite) this inner sense of alienation that he has spoken so candidly about, letting it harden and strengthen him instead.

That right there was why his journey resonated so much with me–rather than shrink from a world that he didnt understand, he fought back and has won again and again and again on every battlefield he elects to choose and in the face of (sometimes incredibly traumatic) setbacks. And he has done it while fighting for others’ causes as well (notably LGBTQ rights, human rights, anti-war, and innumerable other left-leaning causes).

While never being a fan of Black Flag, his solo career has always been a source of inspiration for me, so here follows an exhaustive and as comprehensive as could be mustered ranking of Rollins’ solo music projects, in ascending order.

Henrietta Collins and the Wifebeating Childhaters, Drive By Shooting (1987)

Released in 1987 following Hot Animal Machine, Drive by Shooting is an exercise in provocation. Much more of a piece with Rollins’ stream-of-fruious-consciousness spoken word releases, every facet of it is a pure fury and disgust. At the world, at people, at behavior, at society. Its all molten, seething disdain that is pushed in a half-joking manner. It, rightfully, doesn’t feel so much an official release as an exercise the band did as a laugh (or to exorcise some demons…or both) that then got released.

Unfortunately, none of the jokes really land and the fury and disgust is…a lot. “I Have Come to Kill You” goes on way too long, “Drive By Shooting,” “Hey Henrietta,” and “Men Are Pigs” try to make good points but are too into in their own cleverness and become…uncomfortable to say the least.

“Ex-Lion Tamer” deserved a better release to be on—a punk 'n' roll piece that would have been right at home on a Tony Hawk Pro Skater soundtrack.

Hard Volume (1989)

All of the ferocity you would expect is here for Rollins’ second official outing with his eponymous band. This is easily Henry Rollins at the height of his powers, prowess, and…lets face it…sex appeal. The man is a hunk and he uses every bit of that charisma on Hard Volume, playing with seductive whispers and the obvious double entendres in the before said title track.

Unfortunately where Hard Volume misses most is in its abstraction, abrasiveness, and the repetitiveness of its lyrics. “I feel like this/like this/like this/like this…” becomes somewhat grating after its first few refrains, but when it approaches its second and third minutes of repetition it feels more than a little like beating a dead horse, particularly when the instrumentation backing him is so gripping and dynamic. But the whole album suffers from some editing issues.

While the catharsis is certainly at play, when “Turned Inside Out” devolves into animalistic grunts and screams set to industrial stomps…it goes a little too hard, a little too abrasive, a little too…long. Tracks drag for miles, meandering through tempo changes and following every whim of its creators. That freedom which was so compelling in Lifetime is taken to its furthest extent, frequently to the album’s detriment. As a purely artistic expression its a wild success, but it becomes a bit of a challenging listen.

There are really great moments on this LP—“Joyriding With Frank” (a live release present on releases) is a blast, in particular showing the more fun side that Rollins Band would take amidst all its intensity.

A Nicer Shade of Red (2001)

Unlike it’s companion, the soon-to-be-mentioned Yellow Blues, A Nicer Shade of Red actually feels like a B-sides record. Recorded during the Nice sessions, this is another companion piece that was a benefit release for the Southern Poverty Law Center. Unlike Yellow Blues, however, which confoundingly contains some of Rollins Bands’ best work, A Nicer Shade of Red feels like material that was wisely cut from the Nice sessions.

Never to shy away from difficult subjects, emotions, or language, A Nicer Shade of Red does head into some jarring territory that, lacking context, is not an easy listen. But overall, Red simply feels like filler—chaff that ended up on the editing floor in favor of more compelling songs on its counterpart record. “Your Number is One” also features a bit of a return to the “Liar” style that was the bands breakthrough song.

Turned On (1990)

I wish I had more to say about Turned On than I do. Its a fairly straight live recording around 1989. While undeniably powerful and the band plays as hard as they always did, its a fairly standard live release that in general feels a little like filler in their discography. It just feels…solid all around.

There’s nothing that stands out one way or the other, its just incredibly solid songs played by an eminently capable band. Not a bad thing by any means, but neither is it a standout.

Do It (1988)

Do It is Lifetime’s companion album—three covers recorded during the sessions mixed with live recordings from international shows. The three cover songs are again some of the best recorded material the band has—“Do It,” especially leaves an impression as a bit of a mission statement for Rollins’ life philosophy.

But while Rollins Band live is always a testament to their raw power, here the tribute-named “Joe Is Everything and Everything is Joe” (named for Rollins’ friend Joe Cole, who was murdered during a robbery of their house, an awful event that left a reasonably indelible impression on Rollins’ life ever after) unfortunately leaves an…odd and uncomfortable impression.

After a brief introduction from two dutch hosts, Rollins is in a puckish mood and responds to their lighthearted questions in a jarring way. The performance itself, however, is again a characteristic study in charisma and power as the band roars through Lifetime cuts.

Hot Animal Machine (1987)

While technically this is Henry Rollins’ first solo release (and therefore a proto-Rollins-band project)—recorded and released only months after the dissolution of Black Flag and completed with his characteristic sense of furious momentum—Hot Animal Machine became a part of what was baked into the artistic DNA of a young Rollins, with the phrase often popping up here and there across his career.

No doubt due to proximity, it shares much of its DNA with Black Flag—it sousing overall more like My War era, heavily bass-leading straightforward punk that was right at home with much of what the scene looked like at the time (You can’t tell me that “Followed Around” doesn’t sound exactly like an early/harder Descendents cut). There is, however, too that same spirit of experimentation and flirtation with dissonance that was present on latter Rollins era Black Flag, and something that would continue on throughout his career.

Hot Animal Machine feels rushed, but it also feels like an accurate reading of Rollins as an artist—from the straightforward punk to the bopping rock n roll take of “Crazy Lover,” to the first appearance of “Ghostrider” (Swear to god if they don’t use this for the inevitable Ghostrider show/movie, it will be a missed opportunity).

Insert Band Here (Live In Australia 1990)

While the rest of the performance is exactly what one would expect from their discography, what sets Insert Band Here (Live In Australia 1990) apart is the the absolutely crushing, 14-minute long “Out There,” a lurching beast of a song that borders on sludge metal at times and rivals some of the best stuff of the genre. Seeped in fuzz and fury, the “Out There” crawls like a Melvins-influenced animal with five times the fury and all the ferocity Rollins is known for.

Its a punishing, ecstatic listen that is a shame it didn’t make it onto any of Rollins Band’s LPs.

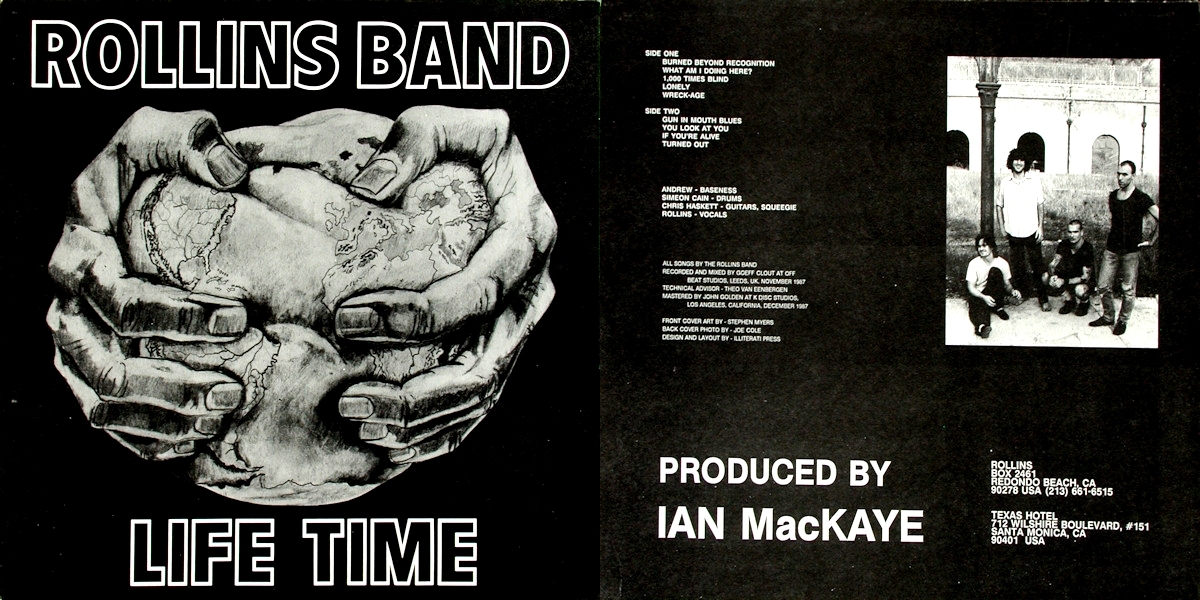

Life Time (1988)

So much of what had already made Hank a force to be reckoned with is present and unleashed in a new and rabid way here. His penchant for blues-influenced lyricism that he twists on its head, his love of super-shredders like (spits) Ted Nugent, and his powerful howl are all in top form. The freedom allowed to follow where his creative winds will, however, lend Life Time a joy and freedom in instrumentation, freed from the bonds of the Black Flag name, as well as a desperation and rush—lyrics tumble out in a rush, touching especially on his ever-present sense of otherness and alienation.

It's an essential effort in his discography, but one that also sometimes wears in the lyrical department. Its really in his backup band, led by Chris Haskett, that this record shines—1000 times Blind manages to go from throat-shredding punk, to blues-soloing, to jazz-influenced whisper and back at the speed of a deadly mechanized animal.

“Lonely,” meanwhile, immediately outwears its welcome in modern times, despite its earnestness, as its self-flagellation seems on its surface a little tone-deaf. While its sentiments are imminently relatable, and its delivery has some of the most piercing screams on the record, its sonic dissonance and lyrics point it out as not having aged the best in 2022.

“Gun in My Mouth Blues” has all the furor and desperation that is most typical of Rollins throughout this era, and has an air of improvisation about it that gives it a feeling of ferocious unpredictability that builds up into an extremely satisfying climax.

A Clockwork Orange Stage: Live At the Roskilde Festival July 01 2000

Similar to The Only Way To Know For Sure, A Clockwork Orange Stage: Live At the Roskilde Festival July 01 2000 was put out in a flurry of releases following Nice. And, as ever, their live recordings are a testament to the band’s power and vitality.

It's a continuous shame that Hank felt like calling it quits because these later live recordings are such an example of how much the band was firing on all cylinders so consistently. Its another overlooked and underrated gem in a discography already replete with classics.

Weighting (2003)

Weighting was billed as a collection of outtakes from the Weight sessions. And while the first couple songs (B-sides and movie soundtrack cuts) fit that description perfectly in their slightly less polished but generally more frantic approach than songs found on Weight, what follows is an extended jam session between Rollins Band and jazz musician Charles Gayle—an legendarily talented free jazz saxophonist with a storied and equally legendary history—and its here that Weighting shines in such a way as to approach sublimity.

While initially the idea of adding Gayle’s free-jazz stylings many might believe could be a jarring mix with Rollins Band’s hard-driving stylings, one must remember how influenced by jazz Rollins Band was—listening to “Liar,” alone, should convince one of this. In practice, this collaboration is something that feels groundbreaking and essential. So often harder genres wall themselves off and isolate in respective subgeneres. While those walls have occasionally been breached, and increasingly moreso, approaching that collaboration as a true sharing of respect and talent with one another from each artists’ standpoints is something that is undervalued in the 2022 era where everything feels blended.

Rather than swallowing or appropriating or imitating the free-jazz form, Rollins Band simply always wore their influences on their sleeve, and in the Weighting sessions, approached Gayle, an artist they clearly adored (and with whom Rollins had previously collaborated on Everything, one of his spoken word albums), on his ground, making space for Gayle to shine and experiment in a way that feels like everyone is having a goddamn blast while doing it.

Gayle, for his part, equally lets the band shine—notably using the tools of his own genre to dance back and forth in the limelight, letting the other musicians come to the fore, reacting with preternatural reflexes to augment and enhance moments of songs before dancing away or come screaming to the fore. The last four tracks are an easy reminder of what a powerhouse the band was live.

Weight (1994)

Weight is another interesting beast in Rollins Band’s discography. It contains 1) their breakthrough single 2) some of the bands best and most impactful songs, and 3) some songs that haven’t aged as well. First things first, “Liar.”

Weight is so impactful because it contains songs which feel like Rollins Band’s raison d’être and is the first time that that reason is really hammered home in such succinct and concrete ways. From “Divine Object of Hatred,” “Civilized,” Liar,” and “Shine,” its never been more clear that Rollins Band, lyrically and musically are simply about impassioned solidarity.

While some tracks in their discography are have aged poorly (See point 3), the good intentions behind them, regardless of the changing context of the world, are burned into every note. So much of his lyrical output has been either about expressing internal worlds for the ostracized and alienated, highlighting inequality, or sarcastically pointing out arguments and turning them on their head to illuminate struggles in others’ lives (see point number 2).

Its here, however, with point 3 that we run into the fantastically poorly aged “Wrong Man,” who’s lyrical refrain presaged one of the poorer movements of the last couple years. While again the band’s intention is clear, the changing context of the world has rendered the track largely tone deaf and unlistenable. On the other hand, “Shine” is easily one of, if not the, best song the band ever recorded. I am not sure there is a more inspirational, impelling, and motivating song that sums up everything about what always made me such a Rollins devotee. In short it is a summary of his own personal philosophy and it will simultaneously scare the life out of you and make you want to conquer the world.

It’s probably somewhat controversial to rank Weight relatively low on the totem pole of Rollins Band’s releases, but on the contrary I think it draws attention to how massively underrated the band has been and how absolutely exceptional some of the oft-passed-over releases of the bands discography is.

The Only Way to Know For Sure (2002)

A nearly two-hour slab of a beast from one of the bands’ latter performances following the release of Nice. While most of that album makes a cut of the 28 (best 28!) live tracks, there is also a heavy peppering of classic Rollins Band tracks throughout. What is perhaps most impressive about this live recording is that the band sounds absolutely massive.

Like they are playing the goddamn Super Bowl. They tear through their set with ferocity, eschewing most of their more abstract songwriting in favor of their biggest rippers. On a personal note, listening to a couple of these live tracks gave me actual chills. If you want a great example of the Rollins Band live, this is it.

Nice (2001)

As a swan song, Nice is one that does make it hurt all the more that Rollins simply ran out of musical inspiration. Nice is a diverse, progressive, and compelling alt rock record. With his typical penchant for melding disparate genre influences into heavy alt sublimity, Nice manages to pull in gospel, funk, free jazz, and more into a head-banging and thought-provoking good time.

Somewhere along the line Hank turned from introspective and occasionally self-pitying lyricism to inspiring and story-sharing aspirational anthems and no record shows his latter-day songwriting better than Nice. While his scream has been tempered into a bellow, the sharpness of his insights and lyrics have not lost any of their bite, replaced with an inspiring circumspection and a desire for his songs to be didactic. And boy howdy does it go off like gangbusters on Nice, despite the leather pants on the albums back cover.

It's also an album with amazingly pleasurable curveballs tossed your way at seemingly every turn. From the bouncy “Up for It” to the driving “Whats the Matter Man,” to the aforementioned free-jazz horn bursts and gospel choirs, to the grin-inducing “Going out Strange.”

Yellow Blues (2001)

Yellow Blues is a compilation of outtakes from the Get Some Go Again sessions. Early ideas for Get Some Go Again involved a mix of the material found there with much of what is found on Yellow Blues. Kicking off with a remix of “Illumination,” Yellow Blues is an interesting beast. Released originally to benefit the Southern Poverty Law Center, it acts as a kind of b-sides record that often manages to outshine some of the band’s best work.

The ever-present experimental flirting is as present here as anywhere, but t contains some of Rollins Band’s most groove-laden work since The End of Silence, its A-side counterpart included. Try listening to “100 Miles” and not jam down the highway doing 90. Despite the album cycle’s contentious background, involving lots of miscommunication and missed connections that led to some hurt feelings on both sides between Henry’s old backing band and the new (did i mention I was an acolyte of his?), both Get Some Go Again and Yellow Blues contain some of my favorite material of his. And while Yellow Blues lacks the immediate punch/catchiness of Get Some Go Again, it more than makes up for it in confident swagger in its first half.

It's at the halfway point that things get a little strange and esoteric and the collection’s nature as a B-side album kicks in. Heavier, more dissonant cuts like “Don’t Let This Be” and “Coma” seem to have far more in common with a fuzzed-out Melvins song than the driving rock that Rollins Band was more known for—full of dissonance and reverb and layers of thick grime. Then it returns to form before ending on the unlisted “Fuck Yo Mama” track which is…certainly something that resembles a song.

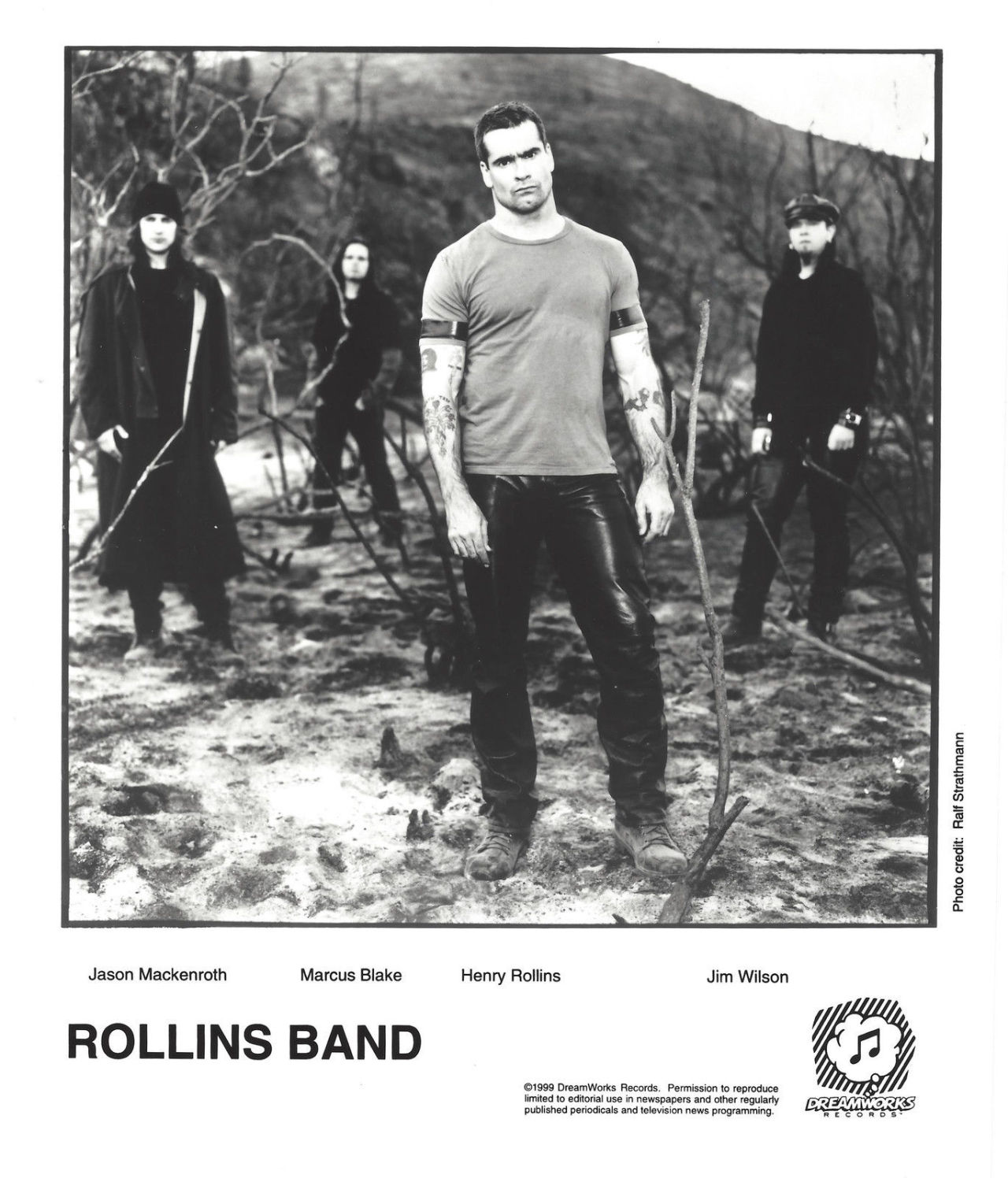

Come In and Burn (1997)

The fifth release of Rollins Band marked the end of an era as it was the last to feature Chris Haskett on guitar and the Sim Cain on drums—both incredible and wildly underrated musicians who’s output across the band’s discography is so phenomenally varied and virtuosically accomplished that listening back through these records is staggering in its accomplishment.

There are few, if any, as hard-driving heavy alt rock acts (or heavy acts in general) who achieved such prominence who’s songwriting can go through such incredible shifts and backflips while still being crushing and surprisingly understated despite its heaviness. Come In and Burn highlights every bit of that talent. From the clairvoyant rollecrcoaster of “The End of Something,” to the shred fest of “Thursday Afternoon.” Lyrically, too, Come In and Burn shows Rollins at some of his finest moments, maintaining some of the rabid wounded animal moments of his youth on early cuts on the record (“Saying Goodbye Again,” “The End of Something,” “All I Want” while transitioning much of his lyrical targets to the inspirational/motivational realm present in some of his best work.

Come In and Burn feels like a friend reaching in and trying to grab you and single-handedly pull you out of a depressive low. Showing empathy, but still dragging you up without remorse or pity. Despite the band firing on all cylinders throughout, however, Come In and Burn strangely doesn’t make as much of an impression as other records in their discography, but is an underrated gem worth reexamining.

Get Some Go Again (2000)

Rollins Band’s return after a brief hiatus, with an entirely new lineup, is so much better than it should have been. The band had gone through years of such a solid and incredible songwriting team that, with Get Some Go Again having nearly all new personnel, should by rights be somewhat wanting. On the contrary: it's one of the band’s best, with the hard-hitting heavy rock outfit operating at the most catchy it perhaps ever was.

Nearly every song on the album is an absolute banger, packing wallop after wallop while still straddling a new, somewhat tempered bellow on the part of Rollins, who here embodies one of the best hard rock front-men of all time. Here he is at his most motivational, his most inspirational and his voice is at his most melodic. For an vocal artist not necessarily known for their vocals, Get Some Go Again is a lesson in rock and roll charisma.

The entire tracklist is marred only by one single blight, the entirely uncomfortable and skippable “Thinking Cap,” which trades in inspiration for judgment in a way that hasn’t aged well, despite again its intentions being advocating for self-acceptance. On the flip side, barring that one exception, Get Some Go Again is Rollins Band’s most consistent release—for the most part favoring straight-forward rock and roll over some of their more experimental dalliances.

The End of Silence (1992)

With little surprise, there is a reason this album is as iconic as it is. From that opening bellow, “I think you got a low self opinion, man…” you are aware that something new is occurring. This is demonstrably different than Rollins’ work in Black Flag. Furthermore, this kind of motivation-core is something that really wasn’t present in a discernible way in ’92, still a far cry from the heyday of melodic hardcore. And from there the album rollicks through hit after hit after hit.

From “Tearing,” to “What Do You Do,” to the showstoppers of “Blues Jam” and “Obscene,” The End of Silence is a string of some of the most extraordinary tracks ever put to record in hard rock, and ones that are oft overlooked in their influence and importance.

***

Help Support What No Echo Does via Patreon:

***

Tagged: black flag, henry rollins, rollins band