During their original 5-year run (1986-1991), Insted were one of the most popular hardcore bands to come out of the West Coast. The Orange County, CA outfit released two influential albums in Bonds of Friendship (1988) and What We Believe (1990), and toured extensively during their time together. Influenced by such bands as Uniform Choice and 7 Seconds, Insted brought forth a melodic yet hard-hitting style of songwriting that has gone on to influence several waves of hardcore.

Insted have reunited for live dates in the years since they broke up, giving a chance to some of the younger fans of the band that didn't get to see them "back in the day."

I was recently on an Insted kick, and went looking for some past interviews with their singer, Kevinsted, aka Kevin Hernandez. Much to my surprise, there really wasn't that much out there, at least online. I mentioned this to Orhun Öner, the guy behind the Life.Love.Shirts book that Revelation Records will be putting out soon, and he gave me Kevin's email address. After a few exchanges, I nailed down some phone time with him, and got the interview.

I found Kevin to not only be open and honest about Insted's legacy, but also very affable during our conversation. I hope you enjoy the interview as much as I did conducting it.

The first thing I wanted to bring up was the lack of interviews you’ve done since the breakup of Insted in the ‘90s. I got the impression that you either chose to keep a low profile, or you didn’t want to talk about “the old days.” Either way, it seems like it was by design.

Well, I don’t know if it was by design. I actually did an interview not too long ago. [Hesitates] I just haven’t had—how do I say this—let’s say interest. I feel like there is a lot of stuff that I’ve read about the band through the years—not stuff that I’ve said—that is just false. It seemed like people were trying to make things into something they really weren’t. You know, saying things like they were at some show, or some event, and I would think to myself, “No, you actually weren’t there.” [Laughs] It’s crazy. I’m not saying that I’m always right, but I would ask other people that I know who were there, and I would say, “Was so and so there?” and they would be like, “No, man, they weren’t.” So I know I’m not crazy.

I think the idea of doing an interview has been a turnoff because of what I like to call all the “false news” that’s out there. If you weren’t there, no problem, just shoot straight. If you were, great. But I saw your website, and it looked cool, so let’s do it.

So, the way I always start the interviews on this site is by getting some background on the person I’m speaking with. Insted came out of the Orange County, CA hardcore scene, but did you grow up there?

I was born and raised in Anaheim, CA. My parents and grandparents were also born and raised there. I even went to Anaheim High School.

Since you’re a third generation Anaheim native, I’m assuming you don’t speak Spanish.

No, I do not speak Spanish. You are correct. My last name is Hernandez, and my father does speak Spanish. He tried to teach me, but as a kid, I was always distracted by sports and music, so I just never picked it up. I wish I had. I would have most likely have picked it up from him.

SEE ALSO: 2017 interview with Andrew Kline (Strife, World Be Free).

You mention being into music at a young age, and because of you’re age, I have to ask you if you were into KISS. I’m a huge fan and they were the first band I ever obsessed over as a kid.

I loved KISS. At the time, the first record I got from them was KISS Alive! I never saw them live, but oh my gosh! I had Destroyer, Rock and Roll Over, all those records. We’re talking the mid to late ‘70s. I wouldn't say that I was a massive fan, but, yeah, they were great.

Who were the bands that were the gateway for you to discover heavier and faster music?

It started with punk and getting into bands like GBH, Subhumans, Peter and the Test Tube Babies, English Dogs, you know, a lot of that kind of stuff. From there, it kind of bled over into the American hardcore like 7 Seconds. Let’s see, the Oxnard bands like Aggression, Stalag 13, and of course, being from Anaheim, the Fullerton bands were also big for me. Those were bands like Social Distortion and D.I.

I remember riding our bikes as kids down to Fullerton to where Social Distortion used to practice. We would stand outside the warehouse and listen to them practice. This was in downtown Fullerton. When they would stop practicing, we would ride our bikes away because we were afraid that they would come out and see us [laughs]. You know, we didn’t want big bad Mike Ness to be pissed at us, so we would ride away [laughs]. Ness was already a legend back then. I’m sure they were approachable, but we were just kids.

Yeah, I remember seeing Harley Flanagan a lot in my neighborhood when I was a kid in the ‘80s, because his aunt lived there, but I was so intimidated by him. It’s like these guys were bigger than life.

Yeah, that’s exactly the same kind of thing with us and Ness. As you get older, you look back and laugh at stuff like that. I’m sure if we had knocked on their door and told them we were fans, they would have probably invited us in.

SEE ALSO: Life's Blood: Born Out of Chaos, Doomed to Failure

What did your parents think of you becoming a punk rocker?

They were supportive. I remember there was this leather jacket that I wanted to get. It was like $100, or something like that. Well, my parents said something like, “If you get $50 up, we’ll pay for the other half of the price.” So they were cool about stuff like that. I don’t want to say they were over-the-top supportive, but the music thing was never really a problem.

Did you have the classic punk look at that point?

I definitely went through a punk phase, yeah. I had the hair spiked really high, bondage pants, creepers, all that stuff. I remember borrowing my friend’s bullet belt one time. So, yeah, it was punk [laughs]. My punk stage wasn’t that long. You know, as a kid, you’re always floating around, you’re finding what you like. But once the straight edge came in, I gravitated towards that and ran with it.

What was the first hardcore stuff you heard? Was it the DC scene bands?

Probably, yeah, the DC stuff, but things weren’t so fragmented back then in hardcore. It was all one. You would go to a show in LA at the Olympic Auditorium and it would be GBH from England, Aggression from Oxnard, D.I. from Fullerton, and Uniform Choice. You went and supported all the bands. It didn’t matter where they came from.

SEE ALSO: When Hardcore Bands Went Hard Rock

Were you ever afraid to go to hardcore and punk shows back then? Especially the LA ones.

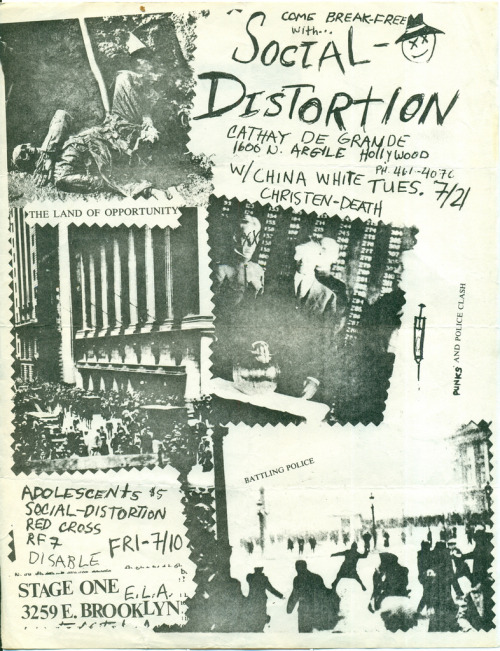

Oh, absolutely. I remember going to a show at, let’s see, I think it was at the Cathay de Grande, and being scared shitless. I also remembering going to see Social Distortion at some basement show with a dirt floor. It was a hotel in El Monte. Well, one of those punk gangs of that time came into the show and a fight broke out. I remember me and my buddies running upstairs and leaving the show. We were so scared. Looking back, it was probably just the whole atmosphere there. Nothing would have probably happened to us, but at the time, we were scared.

What was your first impression of the concept of straight edge?

Well, I loved punk music, but I also loved playing sports. I was a punker who also played basketball on the high school team. These two friends of mine named Chris Smith and Jamie Dominguez were really good friends with [Uniform Choice singer] Pat Dubar. Jamie—his nickname was “Hound”—was Pat Dubar’s catcher on the baseball team at Mater Dei High School. Pat was a very successful high school pitcher and went on to play in college. So they introduced me to Pat. I had already heard Minor Threat and some other bands, but then I learned about Uniform Choice because of the Pat connection.

Was Pat and the other Uniform Choice guys the first people you met who claimed edge?

Thinking back, I would say yes. I’m talking about people that I knew. I obviously knew about Minor Threat and Kevin Seconds being straight edge, but Uniform Choice was the first band I knew from around me that were straight edge.

So you were still in high school at this point. You mentioned being into sports. Did you play on any teams in high school?

I played basketball on the team, yes. I was a guard.

SEE ALSO: 2017 interview with Joey Vela (Breakaway, Second Coming).

Speaking of Pat Dubar, I was recently chatting with Dan O’Mahony (No For An Answer, 411, Done Dying) and he told me that even back in high school, Pat had a larger than life kind of presence, and that, yes, he was an amazing athlete.

I agree wholeheartedly with what Dan O. said. Pat was a stud baseball player back then. I know that Dan went to the same school. I don't think he went there all four years, but he definitely also went to Mater Dei. I can’t speak for Pat, but he was the kind of guy who wouldn’t talk down to you. He was just a great guy. You would have never thought he went to a private school like Mater Dei. I very much looked up to Pat because he was a jock who was straight edge and into hardcore. He was a rebel, going completely against the grain at his school.

What inspired you to go from being just another fan of hardcore to wanting to play in a band?

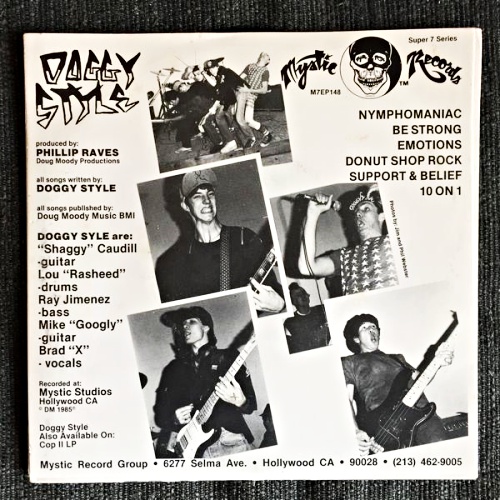

It was just seeing bands like Uniform Choice play live. There was a good friend of mine back then named Brad Xavier who played in the band Doggy Style. That also also had a big impact on me. Brad’s now in that band Kottonmouth Kings. So, anyway, I would go see these local shows back then, and I would know some of the guys in the bands. It was like, “Wow! This is cool. I kinda wanna be in a band, too!”

Why did you decide to become a singer?

Cause I tried playing guitar and could never pick it up. I thought being the frontman and being a leader would be fun. I looked up to Pat Dubar, Kevin Seconds, and Brad Xavier. I could relate to those guys cause I saw them all the time.

How did you go from knowing that you wanted to be in a band to actually starting Insted?

One of my good friends, Steve Larson, was a drummer, and he also an Anaheim High School guy who I used to go to a lot of shows with. Anyway, we are the ones that started the band. I was probably just out of high school, but the other guys were still in high school. We got 7-8 songs together and then started playing parties and garages. It was completely grassroots and from the heart. There was no mission. It was from the heart. We did it because we loved doing it.

Why did you spell the band name without the letter “a” in it?

We were sitting at some ice cream shop in Anaheim on La Palma and we were trying to come up with a band name. We thought, instead of doing wrong, do right, because our message was to be a good person and trying to make a difference. At the time, the letter “A” was circled by a lot of punk bands to make the anarchy symbol, which we knew we didn’t want to use. So we got rid of the “A” to be punk, to be different. I remember us thinking, “instead of doing wrong, let’s do right.”

SEE ALSO: 2017 interview with George D'Errico (Outburst).

Did you have to play cover songs in the beginning to pad the setlist?

No, I don’t recall ever playing a cover. Oh, wait, we did! We played a cover of Doggy Style’s “Donut Shop Rock.” Yes, that’s right.

Do you remember what Insted’s first club show was?

Yes, definitely. It was at a place called Big John’s. We played with Doggy Style. It was a biker bar and we thought it was the shit. I remember couldn’t sleep for three days leading up to the show. It was just the shit.

At what point did Insted really get cooking?

Like I said, when we first started the band, we played parties, and that kind of stuff. When we got [guitarist] Barret [Burt] in the band, he was a kid at the time, and another Ahaheim guy. He was a sophomore at that point. He joined Insted as a second guitar player. I don’t want to say we were telling ourselves that we were going to get all these big shows now, or whatever, but we did take the band more seriously once he joined. We started playing more shows and people seemed to like us. So we wanted to become more of a real band at that point.

How did you guys end up working with Wishingwell Records? Was that just a natural conclusion from being friends with Pat Dubar?

Dan O’Mahony was very instrumental there. He had played our demo and Pat was rocking out to it and he asked Dan, “Hey, who are these guys?” So, yeah, Dan O. was a big advocate for us. He was a good friend who was from Huntington Beach, which was a completely different scene from Anaheim at the time. Next thing you knew, Pat wanted to put out Insted on Wishingwell.

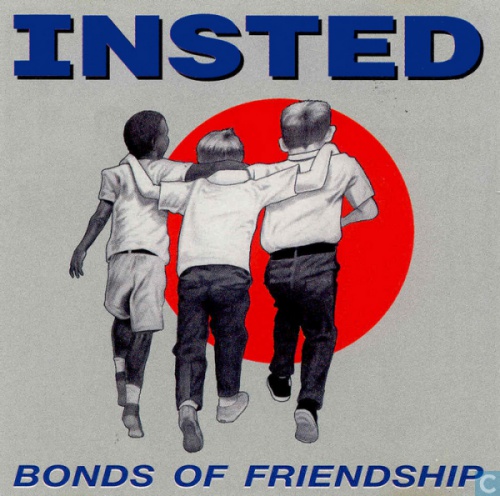

I’m sure a lot of people know this already, but since I don’t, I wanted to ask you about the cover of the Bonds of Friendship album. There’s always been something about that image of the three kids that has resonated with so many people in the hardcore world.

It was a picture from either National Geographic or Time magazine. We somehow saw it and loved it. Then, we had Steve’s cousin [Trent Cotner] draw it. In today’s world, you would probably get sued for something like that [laughs]. But it was punk. It was hardcore. We liked the picture and we had someone draw it. That was it. I also think it represented us. We were friends. Our scene was about friendship. We were nice guys. We weren’t trying to BS anyone. We never said that we lived in alleys, or in a dumpster [laughs]. No way.

Over the years, have you seen some of the bands who have used the Bonds of Friendship cover art and done tributes to it?

Yeah, I definitely have.

What do you think of that?

Oh, I think it’s great! It’s a compliment, of course.

After Bonds of Friendship, you released the We’ll Make the Difference EP on Frank Harrison’s Nemesis Records label. I’ve yet to meet Frank in person, but everyone I’ve talked to that knows him has only said great things about him. That’s rare about anyone.

I first met Frank when he worked at [Long Beach record store] Zed Records. I was talking to our bass player, Rich Labbate, the other day, and we reflect, and really get going. Anyway, we were talking about this. Frank is such a great guy and was always a voice of the hardcore scene. He was such an advocate of our band and supported everything we did. From bringing demos down to Zed and letting us know when they needed more to sell. “Hey, can you bring down so more shirts?” Stuff like that. He helped us out so much, man!

The least we could do when he started his record label was to put something out on it. He was our friend. Sure, I guess at the time we could have shopped it, or whatever. But it was like, we knew Frank would let us use any artwork we liked, and all that stuff, colored vinyl, whatever. It was about helping each other out. Frank is a great guy.

How much touring was Insted doing around that time?

Man, we toured a lot! I remember the first tour we did after the Bonds album was three months. We also did shorter ones where we would fly out to the East Coast. I remember doing that with Vision. We also did some full-length summer tours after that.

Three months in a clip is a lot for a touring band today, let alone back in the late ‘80s.

I don’t know if today’s bands are out there really grinding. Yeah, we would go out for months at a time. Our bass player was good friends with Roger [Miret] from Agnostic Front and we stayed at his house on Staten Island in New York for two or three weeks, parked our van there, playing shows in the area. I remember had these pit bulls in the house. We were grinding. I don’t mean that in a bad way at all. We loved it.

I see these bands these days saying they’re going out on a tour, and then I see that they’re just flying out to California for a few shows. That’s not a tour! What are you talking about?

Did holding down a day job matter at that point?

Nah, it was all piecing things together. You know, part-time jobs, and all that. You would work somewhere for a few months and then quit once you had a tour starting.

SEE ALSO: Best Song on Every Sick of it All Album

Outside of Southern California, was there a region of the country where Insted did especially well, in terms of turnouts and crowd reaction?

That’s hard to say. Of course East Coast shows were bigger and crazier, but I always remember shows in places like Arkansas or Omaha. You would be playing the basement of a bar and there would be 100 people there that were amped that there was even a show happening there. To be honest with you, I kind of preferred the smaller shows. I enjoyed the shows that were off the beaten path. I felt that those people almost appreciated it more. Shit, you would be playing Omaha and there would be punks, skater kids, metalheads, straight edge kids, all hanging out. It was a melting pot and it was fun.

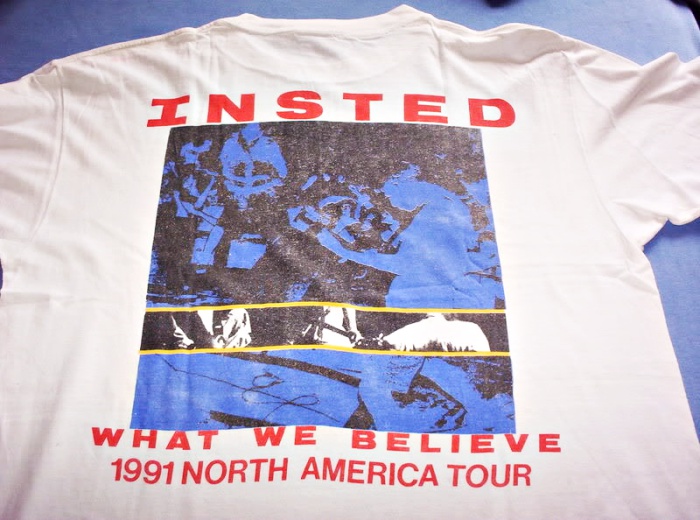

There are a lot of older hardcore folks who complain that there is too much attention put on merch by the current hardcore scene. Where it’s almost more important to some people than the actual music. When Insted was doing all of that touring, were you guys putting a lot of thought and energy into your t-shirt designs, and all that stuff, or was it more of afterthought?

I remember going to shows where the band I went to see would bring a bag of t-shirts and then run out of them really quickly. I would get so bummed out by that. There were also bands who wouldn’t even bring any merchandise. As a band, we always made sure we had shirts and other stuff for people. Even stuff like stickers that they could walk away with. Let’s say a shirt was $8 or something, and some kid only had $6, we would give it to them anyway. If someone only had 50 cents, “Here, take some stickers.” We just wanted people to walk away with something from the band.

But if you were going out for three months at a time, you must have had t-shirts shipped out to you at certain points.

Oh, yeah, definitely. Pat Dubar’s brother, Courtney, did all of our shirts. We would pack our shirts all over our van, until there was no room left for anything. Then we would run out, and Courtney would mail another few boxes out, to say, Roger’s house, or, I remember one time, he mailed some boxes out to Brian Foyster’s house up in Buffalo.

For the What We Believe album, the band signed with Epitaph Records. Now, this was 1990, so the label was already established, but it wasn’t the massive success it would become later in the ‘90s with bands like Rancid and Offspring. How did that deal come through?

[Label owner and Bad Religion guitarist] Brett [Gurewitz] called us and asked if we wanted to be on Epitaph. At the time, there were a couple of smaller labels that were interested in us. We were never approached by Revelation Records, but we wanted to be West Coast, you know what I’m saying? West Coast band on a West Coast label. We loved Bad Religion anyway.

The first record I heard from Insted was What We Believe, and of the two albums, I prefer that one. Now, there are a lot of people who strongly disagree with me. It’s like sacrilege or something.

There’s probably an element of niceness on the Bonds album. We were never an angry band, but as we got older, maybe a little bit of ruggedness came out of us, at least in the Insted way. For Insted, the What We Believe album was definitely more rugged, yeah.

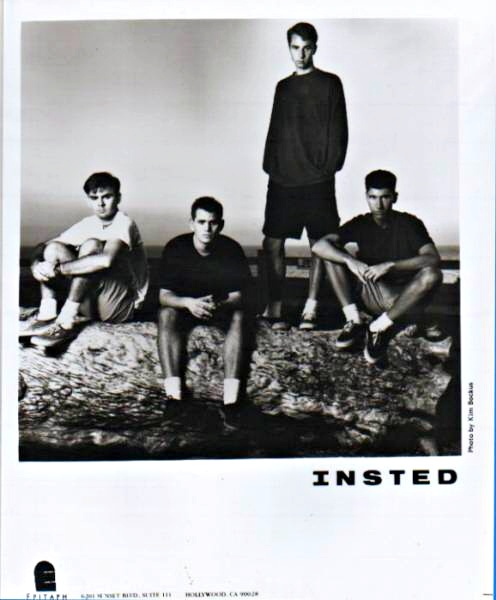

There's that band photo from the What We Believe era of the band where you're all posing next to the van. Where was that taken, and is that the van you guys always toured in?

I think that was taken in the alley behind Rich Labbate’s house. But yes, that was the van we toured in for years. We even put a new engine in it. We were such an active band that we had to have our own van.

Is there anything you would go back and change on either album?

No way. It’s what came from the heart, man. It’s of that time period. I wouldn’t change anything about anything we did on those records. It wasn’t about doing something so certain people could like us, or doing something so that we could sell more shirts. It was so raw. It came out naturally. We were friends and that’s what came from our hearts.

Going back to right after Insted played its final show in the early ‘90s, was there any sense of regret from your point of view, or were you at peace with the whole thing?

I was at peace with it. The scene had changed and money became a big factor. People were like, “Well, we’ll play, but we need this amount of money.” I was like, “What?” I’m not throwing the dart, it was just the way things were heading. People were writing like 4-minute songs. The dress was now like a uniform. It was like this cookie-cutter kind of thing. There was a lot more metal influence in the music because people wanted to do things to get bigger. Also, I was going to get married in a year, and I was always going away on these long tours.

But the most important thing was that we didn’t want to milk it. We wanted to part the way we came in, as friends. We did not take from the hardcore scene, we gave. The hardcore scene gave to us, but we didn’t want to just be takers. I started to see people in bands who were just taking. That’s not why we came into the scene.

Do you keep up with the hardcore scene these days?

I have a buddy named Mike Medina who lives near me who has a crazy music collection. This guy has shirts, records, everything. So, if he calls me and let’s me know about a show coming through town, I’ll go if I can. I hear some newer bands online, that I found out about through word of mouth.

How would you describe your life since Insted? I know you’ve been living in Denver for a long time now.

Yeah, we live in Denver. I’m married with three kids. I work, obviously. Life has been good for us out here.

What brought you to Denver?

A couple of years after we got married, we wanted to buy a house. You know, I was born and raised in Southern California, but whenever Insted toured, I would see these other parts of the country that I thought were nice. I had an aunt who was living in Denver, and whenever we would play there, we would stay with her. At that time in the early ‘90s, Denver was inexpensive. People were cool. It was just beautiful. Well, we couldn’t afford a house in Orange County at the time, so we figured Denver was a great place to live and was affordable. We’ve been here about 25 years. It’s home.

SEE ALSO: 10 Best NYHC Breakbeat Intros

Did you manage to keep a lot of Insted memorabilia? I know I’ve been bad about that for my own band stuff throughout the years.

I have a couple of plastic containers full of shirts, records, stickers, flyers, all that stuff. I used to have a really good record collection with test pressings and rare stuff. I felt bad because I had all of these records that just sat in my basement. So I sold a lot of them to my friend, Mike Medina, and I felt good about it. For one, I knew where the records were, so if I wanted to look through them again, I could. Also, I knew they were going to someone who would love them. I knew he wasn’t going to take the Project X record with the zine in it and then go and sell it on eBay, or something [laughs].

Do your kids care about Insted, and what you guys did? I ask that because I know a lot of my other musician friends’ kids are pretty apathetic to that stuff.

They probably care about it more than I do. I don’t mean that in a sense that I don’t care, but they value it differently. I was just one of the guys, part of the scene. I think my kids think it’s cool. They’ve got the t-shirts that they were once in a while. A long time ago, my daughter’s 8th grade Spanish teacher said he had seen Insted at a Denver show 8-10 years before that. So when I went to the school I brought him a record and he was ecstatic.

How do you feel about Insted’s legacy today?

It was a great time in our lives. I feel that we were fortunate and blessed to be part of that scene and have people that wanted to go see our shows.

That’s great. I really like to hear that.

Yeah, and I know we’ve brought up the straight edge thing earlier in the conversation, and I want to say that straight edge was a great thing for me, as a person. It kinda got blown out of proportion, back in the day. Just because someone isn’t straight edge, it doesn’t mean they are not a good person. Straight edge is good for some people, and for some others, it might not be. Most of my friends today aren’t straight edge, but they’re good people.

You could be addicted to alcohol. You could be addicted to your computer. You could be addicted to your job. You could be addicted to food. It goes way beyond alcohol. I’m always checking myself as a person. If someone is addicted to TV, and someone wants to have a beer, what’s wrong or right? If someone wants to watch 12 hours of TV, or if someone wants to crack open a beer, which one is worse? Well, I think it’s worse to watch that many hours of TV over having that one beer. That’s my opinion.

Everyone in Insted was straight edge at the time. But it wasn’t at the top of the list. I consider Insted more in that 7 Seconds vein. We got lumped into the straight edge thing, but we were more than that.

So you consider Insted more of a positive hardcore band over a straight edge one?

Yeah, absolutely! Positive hardcore was what we did. That’s what I think was unique about us. We had straight edge, punk, metalheads, all kinds of different people at our shows. It was open to everyone. Two out the four guys from Insted are still straight edge today, but that wasn’t the main focus of the band.

Do you drink today?

Yes.

I’ve never been straight edge, so it might mean something different to me, but I know people really pay attention to this subject as it relates to musicians from that scene.

To me, the big thing that I got from straight edge was the anti-addiction thing. Whether it was alcohol, fast food, TV, whatever. It’s the addictive side to things that I was always against. So if someone is straight edge, but they eat fast food seven days a week, you’re probably better off eating healthy and having a couple of beers, or a glass of wine. And look, I’m not advocating having a beer. People should do what they want, but it goes way beyond just having a beer.

Well, I wanted to thank you again for doing this tonight. I had a great time hearing your story.

No, thank you for reaching out. I had a good time. If something else comes to mind, please don’t hesitate to call me.

***

Head to Insted's Facebook page to see more info about the band.

Tagged: hardcore, insted, kevin insted