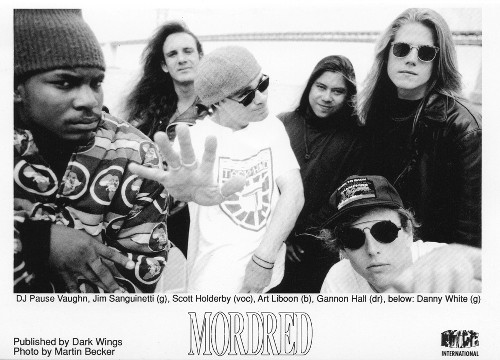

Mordred might have been birthed in the fertile Bay Area metal scene of the '80s, but their sound wasn't that easy to pin down. Incorporating thrash, funk, hip-hop, and hard rock into their songwriting and performance style, Mordred were defiantly original during a time when artistic experimentation wasn't always welcomed. Over the course of three studio albums and one EP, the San Francisco outfit consistently pushed the envelope, finding a loyal following amongst more open-minded listeners along the way.

After some frustrating business issues with Noise Records, Mordred split up in the mid-'90s, but the band is back in business these days, touring when their individual schedules allow. I recently chatted with Mordred bassist Art Liboon about the group's history and his take on people who found their music to be polarizing.

FIrst off, are you a Bay Area native?

I am indeed a native. I was born in San Francisco and lived there until 2013. I've relocated to the East Bay area... more space, less expensive.

What kind of music were you into as a kid?

Apparently, I was really into imitating Tom Jones as a baby, so I've been told; however, I have no recollection of that period. I remember the first record I ever bought was a 45 single of "Catch Me If You Can," which I cannot recall the artist, but it was a radio song about Muhammad Ali. [The song is actually called "Black Superman," and was recorded by Johnny Wakelin in 1975.] That would have been kindergarten through 5th grade, which was awareness of the musical landscape time: soul, rock, jazz, pop, TV music, elevator music, country, blues, classical, etc. I was taking violin and piano lessons during that time, so there was no discriminatory barrier. Not like now, anyway. The barriers and classification analysis started 'round the start of 6th grade.

At what point did you discover heavy music?

My exposure to KISS started in about 5th grade. They were my gateway to other hard rock references, which was useful in connecting with other kids who I would go on to smoke medicine with in the 6th grade. I was taken to my first arena rock concert by my brother-in-law: ZZ Top at Cow Palace. I wanted to like it, but thought it was lame. By the end of 8th grade, I had buzzed hair, wore spiked wristbands, and had already seen a couple of early punk rock shows and movies like The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle and The Decline of Western Civilization. About the start of high school in 1982 was when I became aware of Motörhead and Iron Maiden. Footnote: it was in the 7th grade that my brother finally handed over his bass and amp when he joined the Marines. He gave me his Epiphone EB-3 and a Peavey Century 100.

SEE ALSO: Best Thrash Ballads

What other musical mentors did you have in your life at that time?

Musical mentorship, at the time, could really be attributed to one of my friends' older brother starting in the 8th grade. He knew all the newest and sickest shit. His mentorship always came in a tormentor kind of style by calling me lame for not being aware of the styles and sounds he already knew about. I imagine this was a typical way of learning things underground, growing up at that time.

Did you grow up with any of the musicians we would be familiar with from the Bay Area metal scene?

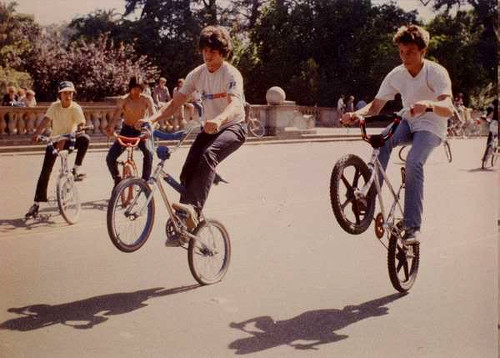

Now that you mention it, the tormentor/mentor was then-drummer now mostly guitarist, Tony Guerrero. His younger brother, Tom, is closer to my age and was a schoolmate at middle school. Their house was a kind of hangout for other kids who were friends to the brothers. We'd play music, skate, ride bikes, drink beer when possible, and cause trouble, but it was mostly harmless fun stuff that kids with spiked wristbands and skateboards do [laughs].

Why do you think you picked bass over playing guitar or drums, and who were some of your influences back then?

I am pretty sure my fondness for bass came from hearing my brother and and his friends play. So, I became aware of bass voicing in music as a kid. I had become aware of its musical function further through piano study and how the left hand is used to voice bass parts in almost all of the compositions I had studied up to that point. When I was given the bass I had already mentally prepared myself on what I was going to do with it. I used a pick at first, but after finding out about Steve Harris, no more picks.

You were one of the co-founders of Mordred all the way back in 1984. Tell me about the way the band first came together. Your first demo had a different lineup than the one that would eventually be on the first album.

During high school, one of the people who I associated with was a transfer student, his name was Josh Juska. He had transfered from a nearby school where his former classmates, Alex Gerould and Stephen Skates, were still enrolled. Through the course of school and checkin' out metal shows, Josh and I both had become aware of each other's musical backgrounds. He was a guitarist. One day he told me that he, Skates, and Gerould were forming a band and they wanted me to audition for a bass player role. I said okay, but nothing happened for a while. Then one day, Josh clued me in on the logistics of how we were gonna play, since none of us had cars except [future Mordred guitarist] Jim Sanguinetti, but he often worked, so we weren't able to make solid plans with equipment and such. So, the first thing was to meet Alex and Steve. When we did, we drank beers, talked about influences, listened to records, had some laughs, and became friends.

Eventually, we would barge in on a guy around our age who lived in Alex's neighborhood and seemed to be having band practice with his own band, or he was auditioning for them or something, he was a metal drummer named Brian Douglas Gilbert. He had like a perfectly polished 70-piece Sonor drum kit packed into a tiny little closet in his parents' basement. I met the other band, they left or hung out, I can't recall, but we got to use their equpment to play a bunch of metal covers. We played Iron Maiden, Metallica, Slayer, Sabbath, and stuff I didnt really know like Exciter and Venom. Nobody knew any of the thrash/punk material that I knew. So that was really when we agreed that we were qualified enough to proceed further. Brian Douglas Gilbert chose not to join us in the Mordred endeavor, and I think Josh was replaced around the time we did actually have a drummer, Slade Anderson, Mordred's first drummer. Sven Soderland is the guitarist who stepped in when Josh stopped coming to rehearsals.

Note: Alex, Steve, and myself would spend four to six months or so playing in Alex's kitchen developing the first few Mordred songs prior to Slade and Sven joining us in the garage.

SEE ALSO: 2016 interview with Troy Dixler (Sindrome).

How did the first album's lineup materialize? I know that a few of you had also played together in another Bay Area band called Mercenary.

Okay, to answer that question I must first reduce the events of those first two to three years into the following: after Mordred's first show at Mabuhay Gardens in February of 1986 with Possessed and Legacy, Sven stops showing up, gets replaced by Jim Sanguinetti, Slade also stops coming, and Erik Lannon takes the drum position. This lineup records Mordred's first multi-track demo tape called Arachne Demo. The band's lineup at that time is Alex, Steve, Jim, Erik, and myself. Meanwhile, Sven, Slade and Danny White are plotting a Mercenary demo with Brooks Holland on bass. Skipping forward approximately six to eight months, and after many local shows, Alex boots Jim for not being fully commited to the band's signature sound, and Danny White takes his place. Shortly thereafter, Skates bails to join the Army. As a result, Mordred begins to wonder how on Earth could Skates be replaced? Skates was a singularity in early thrash at that time, and I for one could not imagine getting some other guy who might attempt to duplicate Steve's presence and sound. I think Alex imagined finding some kind of closer-to-mainstream kook, which I would have opposed. We auditioned some guys and it became clear that we needed someone to make the vocal identity its own singular type of sound, just as Skates had done. This only became apparent to me after hearing Scott Holderby.

Scott was very different from Steve and very different from bands in our local circles, and new enough against that period of what Mordred music was and was becoming. Scott reminded me of a metal kid who had a sort of high snarl roll, which vaguely reminded me of a kind of metal-evolved, Johnny Rotten-ish, TV baby product of the '80s, Volkswagen dune buggy hooligan from some other county. I was sold, and the others agreed, so we began rehearsals with Scott. Then, while getting Scott settled in, Alex announces that he was leaving the band in order to begin law school. Time passes, Lannon doesn't show to practices, gets uninvited back, and Gannon Hall takes the drum position. Hall was known to us because he had drummed in the ever re-emerging then imploding Mercenary group. We get up and running, play more shows, the new members assimilate their own influences easily fusing old proto black metal with proggy guitar school opuses, a new crowd develops, and we are fixtures in the all-powerful East Bay metal brotherhood of bands who came before and after our own formation. One of the bands we enjoyed seeing play at that time was MCM and the Monster. I'm introduced to DJ Pause, and we discuss music like rap, which was relatively new and different at that time. As it was mostly socially conscious, political, and anti-establishment, it was rapidly becoming a mainstream form of music. I liked much of that sentiment in the music, and to hear it spoken in this new way was fresh to my ears. Anyhow, back to the metal: Alex left for law school, Jim Taffer takes his place, Danny becomes the principal guitarist for Mordred and MCM and the Monster, and the monster begins to implode.

How did Mordred come to sign with Noise Records?

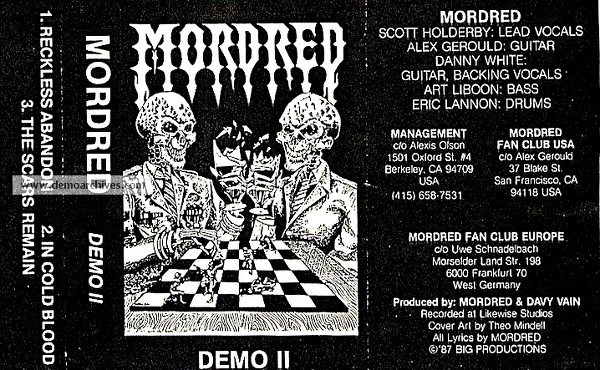

As a joke I started playing "Super Freak" during practice, giggles occurred, we arranged it, and then played it for laughs at a show. Girls then felt welcomed at the thrash shows (kind of). It kinda becomes a party song in the set. Record labels see us, but don't commit. Karl Walterbach of Noise Records hears our second demo which had Alex, Dan, Scott, Erik, and myself on it, and which we had recorded back in 1986. Karl commisions a demo of new material and wants to hear this "'Super Freak' metal music." MCM and the Monster imploded at that time, so we asked DJ Pause to accompany us for the recording of the new demo. He did it, Karl signed Mordred to Noise Records, and then we got to make a record.

Did you have management at that point, and were any other labels interested in the band?

Our management was a friend of the band [Alexis Olson] who became a manager during the period when Skates left and Scott joined. We sent demos and bios to any and all the record labels of the time. At that time it seemed to us that getting signed to a record label was the only option in order to record, tour, and get our music distributed. This was before the web had any reasonably good bandwidth and before computers themselves became as innocuous as they did perhaps 10 years after.

Fool's Game, the first Mordred album, came out in 1989. The album definitely appealed to the thrash side of my listening habits, but there are plenty of stylistic curveballs throughout the record. "Every Day's a Holiday" had a killer groove to it during the verse sections, and it also had turntable work from Aaron "DJ Pause" Vaughn on it. While the video for the song got a lot of airplay on MTV's Headbangers Ball, I wanted to see if you also caught a lot of flack from the more stubborn contingent in your scene.

So, it had been brought to my attention many years after the Mordred 20-year hiatus that some of the bands who we played with, and who always seemed supportive in person, had members who harbored ill will towards our musical methods. It's only hearsay, but I can totally imagine it being true. You must also realize, this is when Metallica had been the biggest band in the world, and by this time for a few years, and just prior to the time when horrible glam metal had been the most popular music. Politically aware rap music was scaring too many normals, and the alienated-sweater-genius rock was about to make people "smart" again or something. So, bands who were rigidly sticking to their archetype for success and puritanically thrash metal, or whatever was their original interpretation of said genre, were not going to have as much of an opportunity to be on the route of getting signed and making records, touring, and overdosing, or whatever was the planned trajectory. The door was closed and it seemed apparent to us that unless you're really better than Metallica, or you have some way to stand out against the mountain of bands who follow that archetype, you'd still have a better chance at winning the lottery. That's how many bands who played thrash during that period felt. I totally empathized with how fucked and corporate things were in terms of getting your music heard by people who might need to hear it. So, to answer your question: yes, I hope there were some angry motherfuckers; if there weren't, the grunge professors who equate heavy metal to Beavis and Butt-Head or Wayne's World have somehow won. See? Distaste for others' musical style is all relative to time.

Was the record label weary of including "Every Day's a Holiday" and your cover of Rick James' "Super Freak" on the album? Better yet, was anyone in the band weary?

Weary on our first record? No, we wrote "...Holiday" in the studio for that record. It was new and different for us to create a metalified estimation of what mainstream hooks might sound like infused with the sound of what was civil disobedience (angry black turntables), while having lyrics be the voice of an overprivileged egomaniac. "Super Freak" was not unfresh to us at that point, no. It did become very much so after our second album had been released. We ended up dropping it from the live set in favor of a Thin Lizzy cover.

How much touring did you do to support Fool's Game?

We toured twice in the U.S. for Fool's Game. Our first tour was with the great Nuclear Assault, who were great to us and who we modeled ourselves after in terms of the headlining band and new support/opening band on the road dynamic. Our second U.S. tour was with the band Overkill. They were great guys and always seemed supportive to us. We learned much from those giants as well. We went to the U.K. and Europe a number of times. The first time was a brief trip. It was mainly for the opportunity to play in Eindhoven, Holland at the 1990 Dynamo Festival. We got on the bill second from the bottom. Scott painted himself blue. The Dutch crowd went berserk during our set. In conversations with the Dutch and Germans, when folks are discussing the many great Dynamo events of the past, 1990 is often still referred to as "Blue Dynamo." When I learned of this, I was shocked and proud for having been remembered for such a weird gimmick.

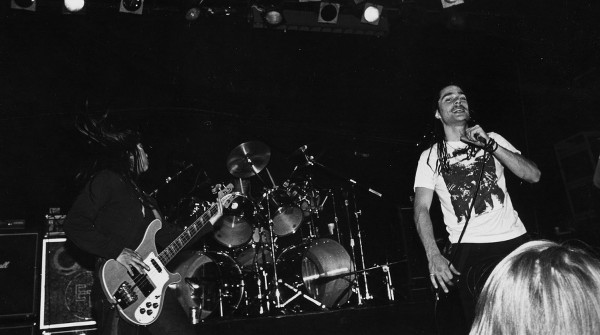

I will also add: if you never saw Mordred live in the '90s, and you consider the music to be some irrelevant form of mall-metal-rapping-doofus music, you're only partially correct; but motherfuckers thrashed their asses off, brutally and without ignorance of what to do in a thrash pit. Some of these examples exist on DVD and the web.

Having a DJ in the lineup was a radical move for a heavy band at that time.

To us it was not radical, but a way to continue to grow as musicians and to learn about how the sampling and turntable voice is placed inside of our band's context. To even make it a point of discussion is to weaken the vitality of metal itself. The species of moron who can't see more than a one-dimensional perspective are typically types who have nothing to add to the community at large. They are what are known as "trolls" in the modern vernacular, and not specifically limited to web-related crap. Some trolls are actually geniuses at web stuff, so not them.

That brings us to my favorite Mordred stuff, 1991's In This Life album. What was the mindset you guys had going into writing the material for that record, and did you set out with any specific goals in mind?

We were a band who had gone through many lineup changes and changed our style after only just establishing it with listeners at home and abroad. The first demo was mailed to people all over the globe for five bucks. We had a tiny yet worldwide following before we had cut a record. We played locally with such bands as Exodus, Anthrax, Suicidal Tendencies, Hirax, Testament, and Death Angel with some regularity, and we enjoyed our first identity. In the second form of the band, which was brought about by necessity, we adapted, added more listeners to our audience, cut a record, gained a bigger following from the metal scene abroad, and some may argue that we were relevent to the genre. All I can say is that we got people coming to metal shows when audiences were beginning to dwindle for many bands. We enjoyed doing it, and our effort to do so was to instigate thrash pits at every performance.

From the very first song, "In This Life," you can hear how much the band had progressed from the debut. There's a sense of maturity in the performances and arrangements.

That song was written mainly by Dan, and then arranged and refined as a group effort in the rehearsal room. We probably added the intro once the main body was fleshed out. I played it as part of a longer, boring tapping excercise I thought was cool. We added the two-part guitar arrangement and probably recorded it on a boom box. That's how a lot of of the material got done in those days. It was quick and dirty.

Your funky bass style really cuts through on In This Life. The song "The Strain" is a great example of that. Outside of Death Angel on their Act III album, I can't think of a band from your world that had such a prominent, funky bass sound on a record.

Okay, thanks, if what you say is a compliment.

It definitely is!

My interpretation of funk in "The Strain" was sort of a way to experimentally fuse what had been traditionally associated with non-thrash formats with the new and unexpected sound of turnable cuts. I used a Trace Elliot preamp and QSC power amp Boogie cabs running directly into the board. I then mic'd the bi-amp 15" speaker to get a low-end frequency refrence so my tone preferences were not missing. I had a Music Man StingRay four-string, poplar body, three-band active EQ.

Another sonic aspect of In This Life that works is the way you worked in the turntablism stuff that Aaron was doing. Did he write all of his parts in the recording studio, or was he in the rehearsal room with you guys hashing that stuff out before the album sessions?

Aaron's parts come together in both environments: at rehearsals and in the studio during tracking. Ideas abound when we're all in one place working together creatively. Aaron's performance skills are astounding sometimes. We can go from just a mental imagining of what could go to tape and after a moment of adjusting and patching connections, it's done and we got it.

For my money, the all-time finest Mordred song, "Falling Away," features on In This Life.

That song is one of our most widely-known songs despite its non-funky feel. Yes, this one was played on MTV on the Headbangers Ball time slot. All of the black and white sequences were shot on an 8mm Bolex camera, and all of the conceptual segments were shot guerrilla-style in one afternoon by our friend Mike MacIntyre, Scott Holderby, and myself. The color portions were shot by our friend, Cindy, and her production company, and I have forgotten her last name.

1992 found Mordred releasing the Vision EP.

I like that EP. It was more of an experimentation and augmentation of what the perceptions were regarding our identity, and an expansion of that idea as we continued to incorporate even more musical styles that we hoped seemed unexpected from us.

You parted ways with vocalist Scott Holderby after that EP. What happened?

Differences in musical direction, communication breakdown, and deteriorating interests in the usual areas of how bands get along over time. At one point he said he was going to leave and it was under respectful and non-bitter terms. The rest of the band said perhaps that it was better than waiting for it to happen later, unexpectedly. We now see that it may have been a bluff and we called it. There's still some disagreement on the exact details, but no one cares anymore, really.

SEE ALSO: 5 Underrated Funk Metal Bands

How did Paul Kimball become Scott's replacement? Paul's style was a departure from Scott's. He had a far grittier delivery than his predecessor.

Paul was auditioned and he was the guy we agreed could make the part his own. That's what he did and we appreciated his skill and attitude in making that record happen. He was indeed a big departure. Like Skates before Scott, we wanted a guy who wasn't some kind of sing-y singer guy. We wanted someone who meant what he sang and sang what he meant, and that's exactly what Paul is. I am proud of his contribution and I'm against many of the haters of that record for what they think they're hearing regarding some weird attempt to align Mordred with something other than what Mordred is.

What was the vibe like within the band when you went into the studio in 1994 to record the third Mordred album, The Next Room?

At this time, [Mordred drummer] Gannon [Hall] took over as manager. We seemed to be moving along okay during the recording. Noise appeared to be giving it a supportive reaction. When it hit the shelves, our strongest fanbase in Germany either shunned the record or didn't know about our forthcoming tour. There were no pre-sale tickets for the tour. Noise pulled the plug on the tour. We said, "Fuck you," by disbanding. We were not bluffing. The tour cancellation and growing tension between Gannon and Karl from Noise led to the ultimate sacrifice: ending the band.

What did you do after Mordred broke up? I know you did some work with the great musician/skateboarder Tommy Guerrero.

Yes, Tom and I had been playing a lot during that period. Gannon and I had a short-lived alternative booze-rock band called Foodstamp, which was fun and the first product to launch on the Function 8 record label. I played in a folk project, some electro-acid jazzy stuff, and I also appeared on a few Function 8 releases as a guest back-up. It was all just stuff to verify what I had known all along: it's only fun if there's a pit.

Well, it's great to have Mordred back!

***

Head to Mordred's official Facebook page to keep up with all of the band's activities.